Teaching the Children We Were

Anti-Racism in Swedish Schools Through the Eyes of a Former Student, Educator, and Advocate

I didn’t wake up one day and decide to lecture in schools about racism. I became the person I needed when I was a child. That’s how this work began.

When I walk into a Swedish classroom—whether it’s a grundskola (primary school), a gymnasieskola (upper secondary school), or a universitetssal (university lecture hall)—I’m not just bringing slides and talking points. I’m bringing my inner child with me.

The quiet Black girl who sat in class wondering why people stared at her hair. The one whose lärare (teachers) were either her safe haven or her daily hurdle. The teenager who left home for university in England carrying a suitcase of unspoken truths—many shaped by the silence in those classrooms, and others by the things that were said aloud.

Like the N-word, repeated by teachers without hesitation, without censorship, and defended as being “i utbildningssyfte”—in the name of education.

It happens in schools across Sweden, even today. But anti-racism education doesn’t make space for violence masked as curriculum. A 2024 report by the Equality Ombudsman (Diskrimineringsombudsmannen) confirms that Afro-Swedish students regularly experience racial harassment in schools, often with no clear path for resolution or accountability. Teachers themselves have admitted to lacking the training to handle racism constructively—despite it being a requirement in the national curriculum.

These moments are why I do this work.

They’re why I now speak not only with students, but in teacher training programs, staff rooms, and policy forums—anywhere there’s a will to build classrooms where no child has to shrink to survive.

My day starts in conversation—with the parts of me that were never heard.

The child who was told she was too loud.

The teen who was too much.

Adulthood doesn’t silence them. It integrates them. I check in with each version of myself, because healing isn’t a destination—it’s a practice. I train. I write. I advocate. But I bring all of me into every room. That’s what makes the work different.

That’s the thing about teaching.

We’re never just speaking to children.

We’re speaking to the children still living inside adults—especially the ones who never got what they needed.

Anti-Racism in Swedish Classrooms Starts on the Playground

The other day, I took my goddaughter to the playground. She’s mixed, autistic, whip-smart, and more emotionally intelligent than most adults. We have matching Afro puffs. I let my inner child out when I’m with her. That’s our space—playful, safe, and ours.

She knows what to say when people ask about her race: “I’m human.” If they push, she knows how to redirect: “I’m my parents’ child.” It’s a script for safety. It’s also a lesson in dignity.

So when a Swedish parent walked up and asked, “What are you?”—she paused, thought about her answer, then remixed it: “I’m baba and mama’s human.” I nearly laughed out loud.

But the adult didn’t stop. She kept going. “Is that your mama?” she asked, gesturing to me.

“No,” she replied. “That’s Lobette.” Kids can never say Lovette—at least not the ‘V’—until they’re older.

Then came the inevitable:

“Where are you from?”

And my godbaby, now done with this recycled script, just wanted to play. So she gave a truthful but too-literal answer:

“Sweden. Mama and baba’s house. [Exact address.] But you can’t come.”

I’ll need to speak to her about that part.

This is Sweden.

This was my Sweden too.

Not much has changed.

And this is why I speak in Swedish schools and parent forums.

Teacher Training on Racism in Sweden: Teaching Adults Who Were Never Taught

I don’t just lecture students. I speak with educators, principals, and parents too. And I’ve learned something essential: when your own inner child is unacknowledged, it’s palpable. You teach from shame. You ask harmful questions without realizing it. You protect silence because that’s how you were taught to survive it.

In fact, a 2022 study published in Teachers and Teaching notes that Swedish educators are required by policy to counteract racism, but many report lacking the training or tools to do so effectively. This disconnect leads to well-meaning teachers unintentionally reinforcing harm—or avoiding the subject altogether.

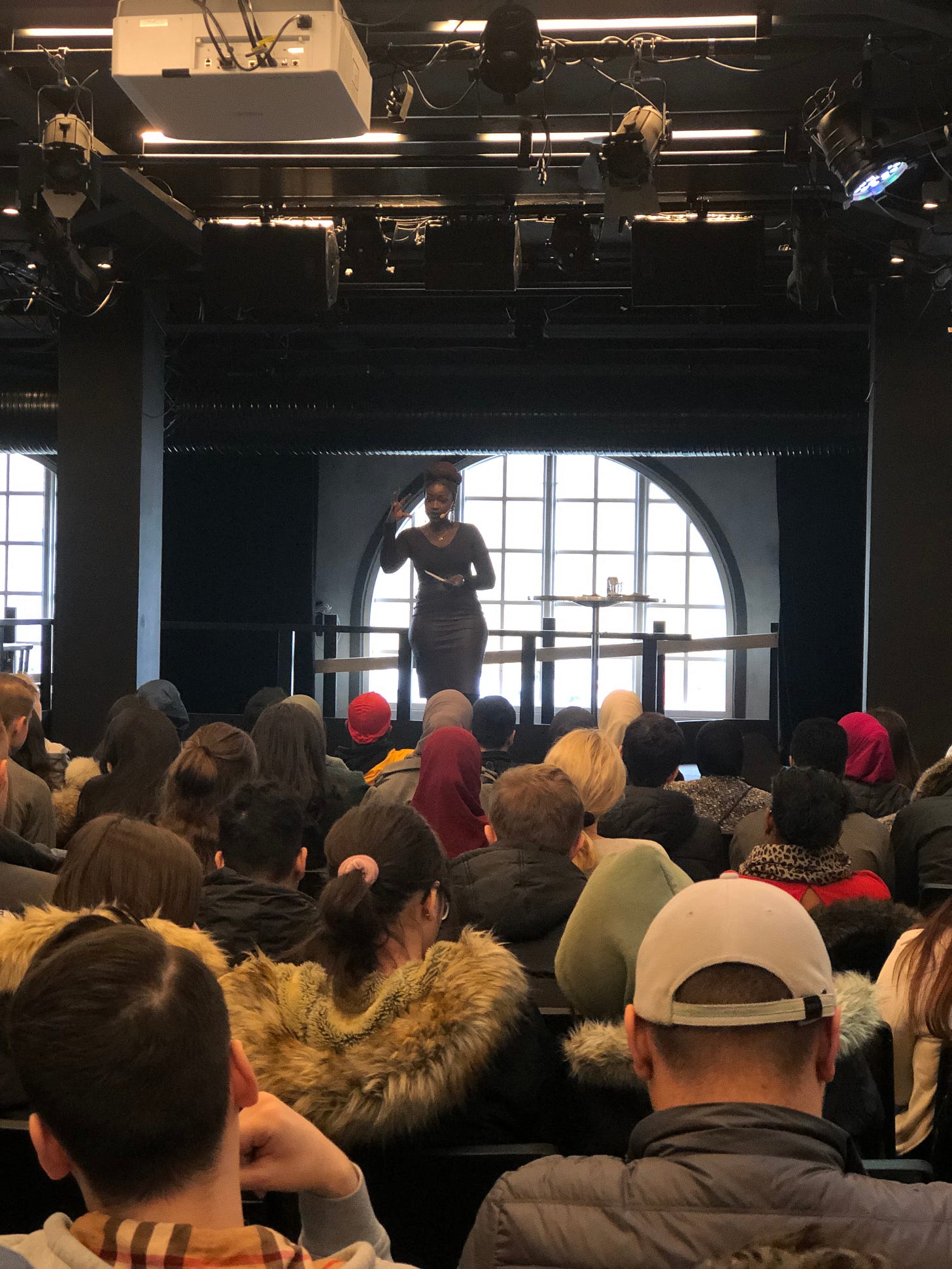

Lovette at Karlstad University

I’ve been invited to lecture across the country—from Karlstad University to high schools and educator events like Lärargalan. I’ve led anti-racism workshops for teacher training programs, sat on panels, and walked into rooms where no one wanted to talk about race—until I said the word out loud. And then everything opened.

I educate because I was educated—by good teachers, good librarians, good friends. And by the ones who failed me, too. They all shaped how I show up.

How Racism Is Taught in Nordic Schools—And How We Teach Something Better

Parents read books to their children at bedtime—books that often reflect nothing of the world those children will meet outside their doors. They talk about kindness, but avoid discussing power. They praise inclusion, but ignore discomfort.

So when those children meet someone like my goddaughter, they ask:

What are you?

Where are you from?

Why do you look like that?

And their parents, standing behind them, either smirk or say nothing at all.

Racism isn’t just learned. It’s inherited.

Not only through history books, but through media, upbringing, and language—the everyday messages children absorb long before they can name them. It’s passed down in which characters are heroes, who gets to be complex, and who is always the sidekick or the threat. It shows up in how parents react when a child names difference. In the tone used to describe someone’s name, accent, or hairstyle. In the jokes left unchallenged. In what is said—and what’s carefully avoided.

According to Sweden’s National Action Plan Against Racism (2024), racial bias is most often transmitted through subtle social cues and structural neglect—making schools a critical site for intervention.

Racism is taught when children hear their parents lower their voice at the mention of another culture.

It’s taught when the news plays in the background and the “bad guy” always looks the same.

It’s taught when a child asks a question about someone’s skin and gets told, “We don’t talk about that.”

These are lessons in silence.

And silence, too, is a language.

You can’t pass on what you haven’t reckoned with. That’s why we must teach not just children—but the adults responsible for them.

Building Inclusive School Communities in Sweden

Not only through history books, but through media, upbringing, and language—the everyday messages children absorb long before they can name them. It’s passed down in which characters are heroes, who gets to be complex, and who is always the sidekick or the threat. It shows up in how parents react when a child names difference. In the tone used to describe someone’s name, accent, or hairstyle. In the jokes left unchallenged. In what is said—and what’s carefully avoided.

Racism is taught when children hear their parents lower their voice at the mention of another culture.

It’s taught when the news plays in the background and the “bad guy” always looks the same.

It’s taught when a child asks a question about someone’s skin and gets told, “We don’t talk about that.”

These are lessons in silence.

And silence, too, is a language.

You can’t pass on what you haven’t reckoned with. That’s why we must teach not just children—but the adults responsible for them.

Community Is the Classroom

My friends chose me as a godparent not just because I love children, but because I see them. I see what’s missing. I help fill the gaps. We are raising our children collectively, the way our ancestors intended. The emotional safety we build between adults is how the children around us thrive.

It’s the same when I step into a school. I’m not just there to speak. I’m there to support educators, youth leaders, librarians, school counselors, and the lunchroom staff—everyone who shapes a child’s world.

Inclusion isn’t about a one-off assembly. It’s about culture-building across every layer of the school system. According to the Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket), improving school climate and educator accountability is one of the most effective ways to reduce racial bullying and discrimination. Yet many schools lack the resources or confidence to act—especially when it comes to intersectional issues like race, disability, and migration.

Parents alone can’t do it all. And blind spots, when unexamined, become generational.

Previous post on parenting

Anti-Racism Workshops and School Talks in Sweden

I provide anti-racism lectures, workshops, and training sessions—grounded in lived experience, neurodivergence, intersectionality, and joy.

I work with:

Students (middle school, high school, university)

Teachers-in-training and faculty at universities

Parent groups and PTA meetings

School leadership and policy teams

My public speaking is available in English or Swedish and integrates trauma-informed practices, equity-centered pedagogy, and systemic analysis. I teach educators to move beyond “kindness” into policy, beyond performance into practice.

This work isn’t theoretical. It’s tied to measurable outcomes: more engaged students, reduced disciplinary bias, better support for racialized children, and more confident staff. Schools I’ve worked with often report long-term shifts in how race and belonging are discussed—not just in the classroom, but in staff rooms, parent dialogues, and school policy.

From classroom tools to structural insights, I bring clarity and language where silence once sat.

You’ll find my work cited in Feministiskt Perspektiv, Värmlands Folkblad, and across national forums for education and inclusion.

If you’re an educator, policymaker, or school leader working to bring anti-racism education into Swedish classrooms, this is for you.

Maybe you’re revisiting your teacher training curriculum and looking for ways to address systemic racism in schools. Or you’re seeking new strategies for building diversity and inclusion into Swedish education—not just through representation, but through structure, language, and accountability.

Perhaps you’re exploring intersectional approaches to race and belonging in Scandinavian classrooms, or trying to find practical tools for addressing racial discrimination in Nordic school environments.

Wherever you’re positioned, I hope this piece offers more than language. I hope it offers clarity. And a path forward.

Legacy and Love: Building Something Bigger

I’m building a school for autistic children in The Gambia.

It’s not just infrastructure—it’s legacy. A space where neurodivergent children can learn without shame, isolation, or misdiagnosis. Where Black autistic children are met with care, not control. The school will center community, language, and culturally competent support.

I don’t have children of my own—but I’ve been mothering for years. I mother my inner child. I mother the students who whisper their truth after the bell rings. I mother the children in my life whose questions deserve real, expansive answers. We say the next generation will be better. But they won’t be—unless we are.

Anti-Racism Training for Schools, Universities, and Educational Leadership

I deliver structured lectures and staff training designed to help institutions identify, address, and dismantle systemic racism in education. Trusted by educators, policymakers, and leadership teams across Sweden, my work centers on building inclusive, accountable systems—not surface-level fixes.

Who is Lovette Jallow?

Lovette Jallow is one of Scandinavia’s most influential voices on systemic racism, intersectional justice, and human rights. A nine-time award-winning author, keynote speaker, lecturer, and humanitarian, she specializes in neurodiversity, workplace inclusion, and structural policy reform.

As one of the few Black, queer, autistic, ADHD, and Muslim women working at the intersection of human rights, systemic accountability, and corporate transformation, Lovette brings an unmatched perspective rooted in both lived experience and professional expertise. Her work bridges the gap between theory, research, and action, helping organizations move beyond performative diversity efforts toward sustainable, structural change.

She has worked across Sweden, The Gambia, Libya, and Lebanon, tackling institutional racism, legal discrimination, and refugee protection. Her expertise has been sought by global publications like The New York Times, on high-profile legal cases, and by international humanitarian organizations, where she has provided critical insights on racial justice, policy reform, and equity-driven leadership.

As the founder of Action for Humanity, Lovette collaborates with businesses, policymakers, and institutions to develop equity-centered solutions that are practical, measurable, and embedded in long-term strategy.

Follow Lovette Jallow – DEIB Strategist, Keynote Speaker & Humanitarian:

Website: lovettejallow.com

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/lovettejallow

Instagram: instagram.com/lovettejallow

YouTube: youtube.com/@jallowlovette

Substack: open.substack.com/pub/lovettejallow

Twitter/X: twitter.com/lovettejallow

Action for Humanity: lovettejallow.com/action-for-humanity

Action for Humanity Instagram: instagram.com/action4humanity_se

Reading this text brought me to tears. You have found words to my experience growing up in Germany. It is the subtle lowering of the tone, the insistence of we don't see colour, the frequent use of the N- word, the images, movies that transport clear messages yet stay unchallenged that makes this experience so painful. Thank you for writing your truth down. It validates my experiet and encourages me to write ❤

Wow Lovette, I resonate with this so much. I was an educator for several years and currently creating a workshop/curriculum to highlight the need of allowing children emotional processing and bodily autonomy. When you said "Adulthood doesn’t silence them. It integrates them." like YES! Our innerchild is often the reason we are triggered by children. I hate that racism is so global. Like dang can we just live!

I really appreciated this piece because I have never gained insight on the experiences of Black folk in Sweden. I love that you advocate for your innerchild and children still in body. Also, your goddaughter sounds fun! That's how I am with my nieces too. And the closing line, "That’s why we must teach not just children—but the adults responsible for them" is so important. Children will be okay when the adults are okay and right now, adults are not okay. But there's hope and intentional work! I'm inspired.