Black Women in Sweden: Erasure, Media Bias & the Fight for Representation

Who Gets to Represent Blackness? The Role of Colorism in Swedish Media

Black Representation in Sweden: Who Gets Seen & Who Gets Erased

When people outside Sweden picture the country, they often imagine a homogenous, all-white population, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Sweden today is one of the most diverse nations in Europe, with 35% of the population having one or both parents born outside of Europe. By 2025, the country will have over 600,000 Black Swedes, yet the dominant image of Sweden—both internally and externally—rarely reflects this reality.

Despite this, the face of Swedish media, history, and storytelling remains overwhelmingly white, and that of Black swedes at best, is biracial. Of the half a million Black Swedes, only 35,000 are mixed-race—yet they dominate representation in everything from fashion campaigns to discussions on race and diversity. This isn’t by accident. It reflects an unspoken rule in Swedish society: Blackness is only acceptable when it aligns with Eurocentric beauty standards.

This selective representation has excluded dark-skinned Black women, reinforcing a gatekeeping of Blackness where only the most palatable versions of Black identity are seen and celebrated.

Why Representation Matters: Goodnight Rebel Girls & Svenska Hjältinnor

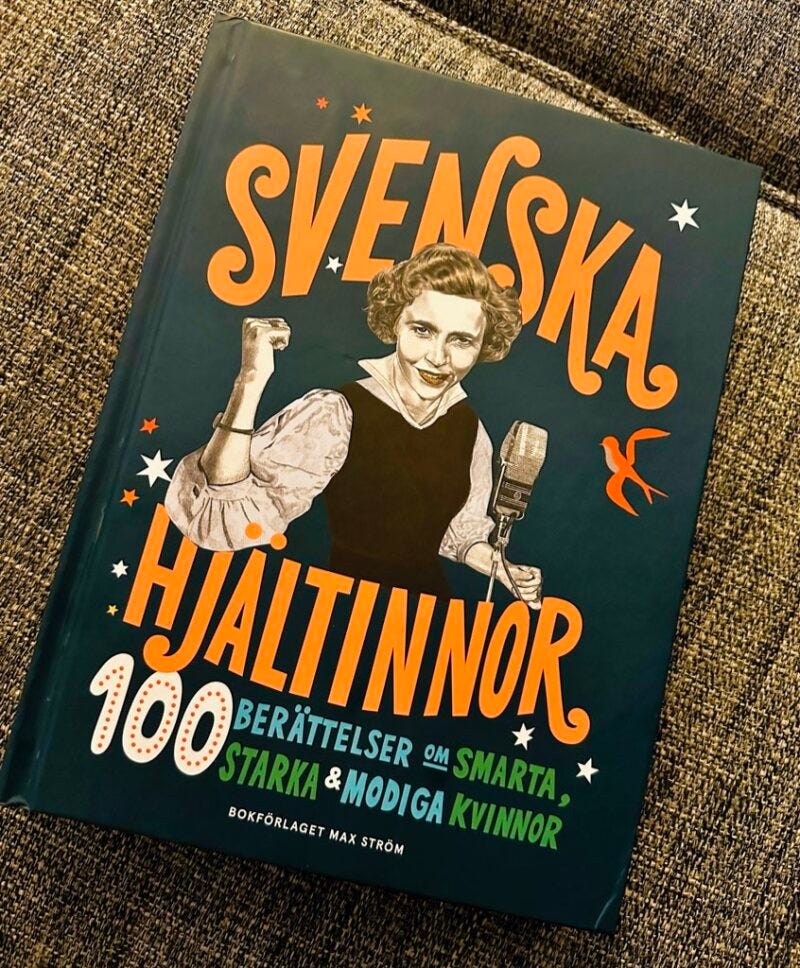

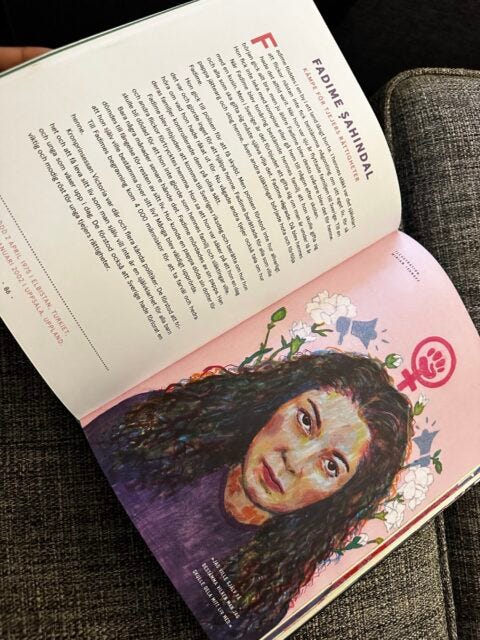

I have always loved the Goodnight Rebel Girls book series and often read them to my nieces and godbabies. It’s a series that celebrates women who defied expectations and reshaped history, and I admired the way it empowered young girls. So I was thrilled to be featured in the dedicated edition for young Swedish girls, Svenska Hjältinnor (Swedish Heroines), published by Bokförlaget Max Ström.

But my inclusion in this book is not just a personal achievement—it’s a statement about visibility in a country where Black women, especially those with dark skin, have historically been excluded from narratives of success, heroism, and leadership.

For me, growing up in Sweden meant rarely seeing dark-skinned Black women in books, on TV, or in leadership roles. The narratives that surrounded me—on television, in history books, and in classrooms—rarely included people who looked like me, lived like me, or shared my experiences. When Black representation did appear, it was almost always light-skinned individuals who fit Eurocentric beauty standards, reinforcing the unspoken rule that visibility was conditional on proximity to whiteness.

This lack of representation wasn’t just disappointing—it was harmful. Without stories that reflected my identity, I internalized the idea that my existence in Sweden was peripheral, secondary, almost invisible. The absence of representation dictated societal hierarchies—determining who was valued, who was included, and who was forgotten.

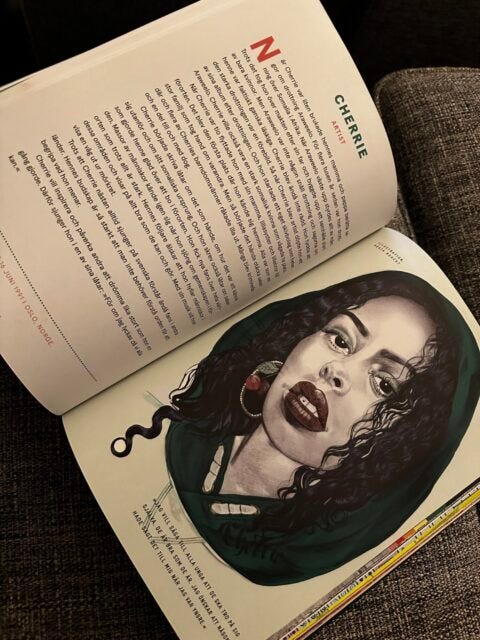

So imagine my surprise when I was included in Svenska Hjältinnor, This book pays homage to 100 extraordinary Swedish girls and women from different eras who have achieved remarkable things. Among them are renowned figures such as author Selma Lagerlöf, my late mentor, the psychologist and Holocaust survivor Hédi Fried, and Astrid Lindgren, whose book “Pippi Longstocking” I read in Gambia long before moving to Sweden when I was 11 years old. I—a Black woman, an author, an advocate, a disruptor—was named one of the Swedish heroines, an honor that aligns with the annual recognitions I’ve received since 2016, when Swedish newspapers began naming me one of Sweden’s 100 Women Changemakers on International Women’s Day. But as you’ll see, this isn’t just about accolades—it’s about why representation, especially for Black women in Sweden, has been so limited in the first place.

This is not just a personal milestone; it’s a moment of cultural significance. It’s a testament to how much representation matters—and how, despite the odds, I carved out space where none existed before.

In this post, I’ll share my journey from invisibility to recognition, the challenges of representation in Sweden, and what this moment means for future generations of Black girls growing up in a country that has yet to fully embrace them.

The Lack of Black Representation in Sweden and its Impact

As a child, books were my escape—a way to imagine a world beyond the limitations placed on me in Sweden. But no matter how many pages I turned, I never saw myself reflected back.

When I was growing up in Gambia, my grandmother recognized my love for books and built me my own library. She didn’t just fill it with stories of Black children or African folktales—she stocked it with books that featured people from all over the world. She wanted me to understand that humanity is diverse, and so are its stories. Because of her, I never saw difference as strange or foreign—it was simply a part of life.

So when I was six years old and we visited my mother in Denmark, I wasn’t in awe of the Danish people—but they were certainly in awe of me. It was the same when I eventually moved to Sweden. I wasn’t the one surprised by them—they were surprised by me.

And yet, for a country that held such an air of intellectual superiority, I was struck by how little they seemed to know about the rest of the world. This became painfully clear when I went to the library. I expected books to reflect the global landscape my grandmother had prepared me for—instead, I found stories centered on a single, narrow version of Sweden.

Swedish children's books centered whiteness. Black characters, if they appeared, were sidekicks or stereotypes—figures of struggle, never of triumph. They weren’t heroes. They weren’t history-makers. Their presence served whiteness, reinforcing who was valued and who was forgotten.

I remember standing there, staring at the shelves, thinking: How poor was their world that fully fleshed-out characters never bore a skin tone different from a talcum tournado?

How ironic that a country that prides itself on global awareness could not see beyond its own borders—even in its literature. And how ironic it would be when they, the adults and children alike, would later be shocked at their own ignorance—not because of anything I had done, but simply because I existed outside their narrow expectations.

Beyond Books: The Limits of Swedish Representation

This lack of representation wasn’t confined to literature—it extended to Swedish media, history, and leadership roles.

Black women were almost nonexistent in public life, and when they were present, they were almost always light-skinned and mixed-race. It didn’t take long for me to internalize the unspoken rule:

Blackness in Sweden was acceptable—but only if it was diluted.

My womanhood, my race, my voice—all had to fit within the comfort of whiteness.

This wasn’t just about who appeared in books or on screens—it was about who was allowed to exist visibly and be recognized as part of Swedish society.

The lack of representation didn’t just reflect social hierarchies; it reinforced them. It dictated:

Who was valued.

Who was heard.

Who was forgotten.

Without role models who looked like me, how was I supposed to believe that I could become anything beyond what the world expected me to be? I was lucky I had a background that reinforced and validated me from west africa but what if I didnt…

Sweden’s Media Problem: Why Dark-Skinned Black Women Are Erased

This wasn’t just about who appeared in books or on screens—it was about who was allowed to exist visibly and be recognized as part of Swedish society. The lack of representation didn’t just reflect social hierarchies; it reinforced them. It determined who was valued, who was heard, and who was forgotten.

And for young girls like me, that erasure had consequences.

Representation shapes how we see ourselves and the possibilities we believe are open to us. As a young Black girl in Sweden, I rarely saw role models who shared my experiences—not until I moved to England for my university studies did I finally encounter Black women who lived without the constant pressure to shrink themselves to fit within whiteness.

In Sweden, at best, I saw mixed women on television—women whose experiences did not mirror mine as a dark-skinned girl. Colorism impacts us differently, and Swedish media has long favored those closer to their skin tone. Unless you fit the stereotypes set out for you, visibility is not an option.

Colorism in Sweden: Who Gets to Represent Blackness?

Colorism, the preference for lighter skin tones within the same racial or ethnic group, has long shaped representation in media and society. While this is a global issue, in Sweden, the effects are particularly pronounced.

Swedish media, when it does acknowledge Blackness, defaults to lighter-skinned, biracial individuals as the acceptable face of Black identity. This selective visibility does more than skew public perception—it reinforces the idea that only certain versions of Blackness are palatable to the Swedish audience.

The consequences go beyond media representation. When dark-skinned Black people—especially women—are erased from the public eye, it signals to society that their stories, experiences, and presence are unimportant. This not only shapes how institutions treat us but also how we internalize our own worth.

Media representation isn't just about visibility—it’s about power. When only lighter-skinned individuals are given space, it fuels a cycle where dark-skinned Black Swedes are excluded from opportunities, erased from narratives, and forced to fight for even the smallest forms of recognition.

Challenging Swedish Beauty Standards: The Creation of Black Vogue : Skönhetens Nyanser

Growing up in Gambia, a country where Blackness is the majority, we were never so narrow-minded as to believe that the world ended at our borders. My grandmother, knowing the power of books, built me a library filled with stories from across the globe. I read about people of different races, cultures, and backgrounds—not because she was “progressive,” but because that was simply how you prepared a child for the world they would navigate.

So when I first traveled outside of Gambia—to Denmark at the age of six, and later to Sweden—I was never surprised by the people I met. But they were surprised by me. The world I had been taught about was vast, interconnected, and full of different perspectives. Yet, the world they had been given—the one reflected back at them through their books, media, and institutions—was small, homogenous, and built only in their image.

In Sweden, I found bookshelves lined with the same pale faces, the same Eurocentric stories, the same exclusionary ideals. A country that prided itself on being educated, modern, and globally aware had somehow failed to reflect the very world it claimed to lead.

This isn’t an issue of ignorance—it’s an issue of choice. The West presents diversity in children’s books as something to be debated, something radical, something “woke.” Books like Antiracist Baby exist not because inclusion is new, but because white parents must be reminded to prepare their children for a world that has never been exclusively theirs. They call it an agenda, but what is more ideological than raising children to believe only their stories matter?

I refused to accept that reality. If representation didn’t exist, I had to create it myself.

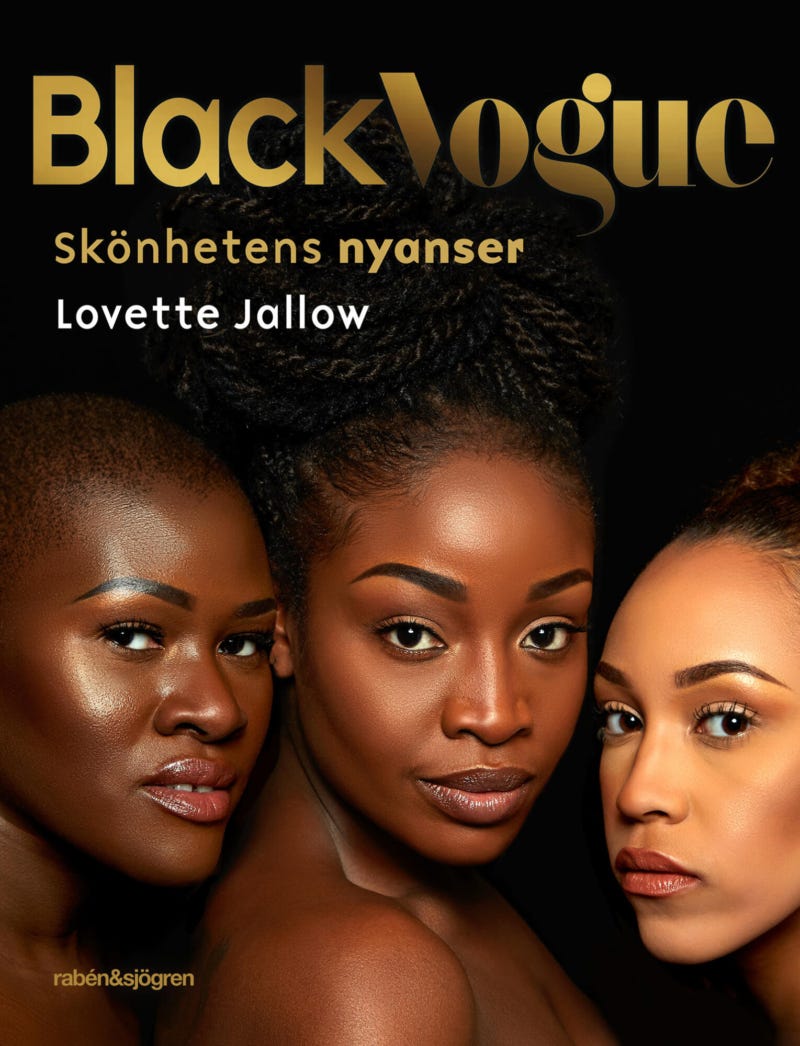

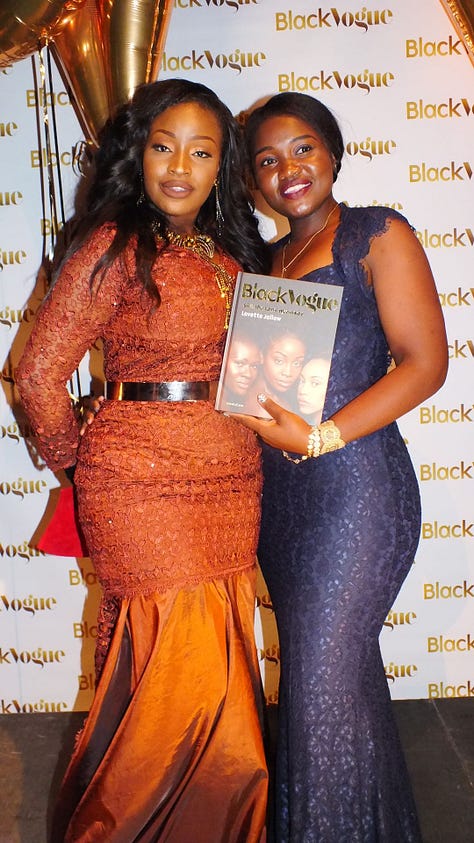

That’s why I wrote Black Vogue: Skönhetens Nyanser (Beauty Shades). More than a book, it was a statement—a response to years of exclusion and a necessary resource for Black people seeking visibility in a country that had erased them. It celebrated Black beauty in all its shades, rejecting the mold set by Swedish media and beauty industries.

But Black Vogue didn’t just tell a story—it became a movement.

A Shift in Scandinavia’s Beauty Landscape

Black Vogue: Skönhetens Nyanser quickly became more than just a book—it sparked a movement in beauty diversity across Scandinavia.

For the first time, Black Swedes saw a reflection of themselves that wasn’t distorted to fit whiteness. It challenged the narrow, rigid beauty standards of Scandinavia, proving that Blackness is diverse, complex, and worthy of celebration. By directly confronting the exclusionary beauty norms perpetuated by Swedish media, the book helped broaden society’s acceptance and appreciation of diverse beauty.

It wasn’t about asking for space—it was about taking space.

This movement has inspired many Black Swedes to embrace their unique features and reject the limiting stereotypes that have long dictated who is considered beautiful in Sweden.

Representation isn’t just about visibility—it shapes self-esteem, identity, and opportunity.

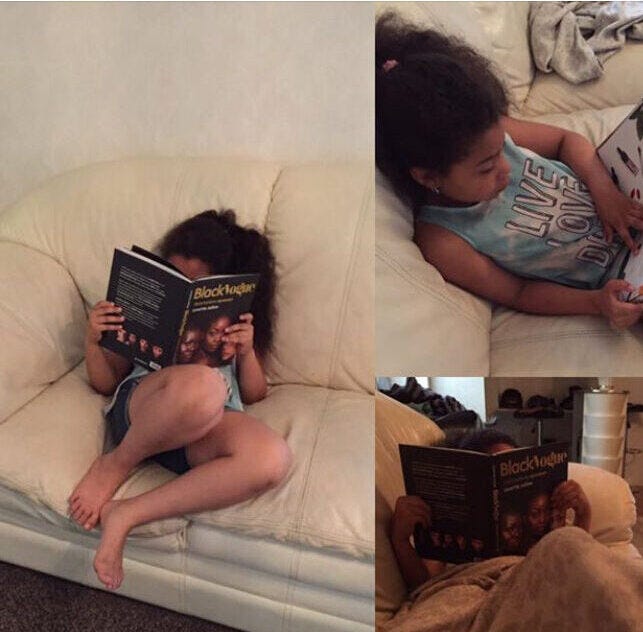

Studies confirm this: when children see themselves positively reflected in media, they develop higher self-esteem, better academic performance, and broader aspirations. When representation is limited or distorted, it reinforces exclusion and limits what people believe is possible for themselves.

By creating Black Vogue: Skönhetens Nyanser, I aimed to fill the void in representation that I experienced growing up—to provide a platform where Black beauty could be seen, celebrated, and appreciated in all its diversity. This work continues to inspire and empower the next generation of Black girls in Sweden and beyond.

More Than a Book: Advocacy and Industry Pushback

Since returning to Sweden after 10 years in England in 2013, my work has been centered on creating space where Black voices, stories, and expertise are recognized—not just tokenized.

I became a public speaker, educating workplaces, schools, and organizations on intersectionality, neurodivergence, and racial bias.

I wrote Black Vogue, not just as a book but as a cultural intervention in Scandinavia’s beauty industry.

I built platforms where Black Swedes could see themselves, refusing to let us remain a footnote in history.

But even as Black Vogue gained recognition, I saw firsthand how Sweden treats Black visibility—with superficial inclusion that still seeks to control our image.

The fight for representation isn’t just about visibility—it’s about who controls the narrative, who gets to tell the story, and whose face is considered worthy of being seen. And that is a battle I refuse to stop fighting.

The Outcome: From Invisibility to Swedish Heroine

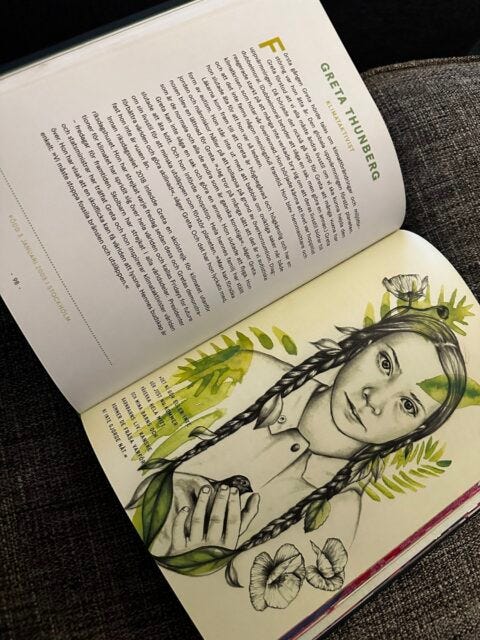

In 2023, I received an email. Svenska Hjältinnor (Swedish Heroines)—a book honoring 100 Swedish women who have shaped history—was including me.

My name now sits alongside Swedish icons like Astrid Lindgren, Selma Lagerlöf, and Greta Thunberg.

For a country where Black women have long been erased, my inclusion in this book is a shift in the narrative. It is proof that no matter how hard a society tries to overlook us, we will always find ways to take up space.

But here’s the hard truth: I shouldn’t have to be exceptional to be seen.

Representation shouldn’t be an exception—it should be the norm.

Key Takeaways for Readers: The Importance of Representation

This moment is bigger than me. It speaks to a larger conversation about power, belonging, and who gets to be remembered.

1. Representation Shapes Identity

Seeing yourself reflected in books, media, and leadership reinforces that you belong, that you are worthy, and that your voice matters.

When marginalized communities are excluded from history, they are also excluded from the future.

2. You Can’t Be What You Can’t See

Studies show that positive representation in media and literature directly impacts career aspirations, self-esteem, and mental health.

When young Black girls in Sweden see a Black woman recognized as a Swedish heroine, they understand that they, too, can shape history.

3. Representation Isn’t Just About Visibility—It’s About Power

It’s not just about having Black faces in books—it’s about ensuring that Black people have decision-making power in publishing, media, politics, and society.

True diversity means inclusion at all levels—not just being featured, but being in positions where we control the narratives that define us.

From Tokenism to True Inclusion

My name in Svenska Hjältinnor is not just a personal achievement—it is a challenge to Sweden’s publishing industry, media landscape, and educational system to do better.

Representation is not just about who gets to be in the room, but who gets to write the story.

My presence in this book is a crack in the system, but it is not enough. Until we see Black women consistently recognized for their achievements—without having to fight for inclusion—true progress has not been made.

A Moment of Recognition, A Call for Accountability

Svenska Hjältinnor is a beautiful book, but it is also a reminder of how far we still have to go.

It is an honor to be included among such remarkable women, and I hope this book—along with my own work and those that follow—continues to inspire future generations to dream bigger than the limitations placed upon them.

But we must also be honest about the work that remains.

The Swedish Publishing Industry’s Diversity Problem: A Call for Accountability

The issue isn’t just who is included—it is who controls how we are depicted.

I also hope that Max Ström and the broader publishing industry in Sweden work diligently to enhance their diversity efforts, not just in the pages of their books, but behind the scenes and within their workplaces.

It is not enough to feature diverse voices—there must be diverse decision-makers.

This would prevent the kinds of oversights that require emotional labor from those of us fighting to be represented accurately. When I saw my own illustration, my skin tone had been depicted six shades lighter. My features were altered to resemble one of the white artists who contributed to the book, only with a darker tint and a headwrap.

This wasn’t just a mistake—it was a reflection of a system where Black representation is still filtered through whiteness.

These issues, likely missed by non-Black employees and illustrators, required correction by me—a burden I would have gladly avoided if true diversity had existed behind the scenes.

The Swedish publishing industry has a diversity problem—one I will address in another article. For now, I want to celebrate this forward movement while making it clear that inclusion must go beyond symbolic gestures.

Until we see a Swedish literary industry where Black authors, editors, illustrators, and decision-makers are present at all levels, representation will remain conditional rather than systemic.

This is a step forward, but it is not the finish line.

Images from the free Black-centered events I’ve organized, bringing together over 3,000 Afroswedes—Black Swedes of all shades—to celebrate ourselves, our beauty, and our community. Because as my grandmother taught me, other people's limited definitions should never define your expansiveness.

Who is Lovette Jallow?

Lovette Jallow is a 9 time award-winning author, speaker, and advocate specializing in neurodiversity, intersectionality, and human rights. As a Black autistic queer disabled woman, she has built one of Scandinavia’s largest separatist networks for Black women while championing equity and mutual care within marginalized communities. Lovette uses her platform to challenge societal norms, empower others, and redefine what authentic, inclusive communities look like.

Learn more about Lovette’s work at www.lovettejallow.com.