Neurodivergence in Ancient Africa: What History Forgot but Our Ancestors Knew

How West African societies embraced autism, ADHD, and neurodivergence as spiritual gifts and communal roles—long before diagnosis existed.

Neurodivergence Was Supported, Not Pathologized

In ancient West African societies, neurodivergent people weren’t seen as broken—they were healers, memory keepers, griots, and seers.

“We are your ancestors returning. We are part of the brain’s ecosystem, not to be pathologized.” — Lovette Jallow

© Lovette Jallow. All rights reserved.

This section is part of a protected and copyrighted body of work. It may not be reproduced, excerpted, adapted, or cited in academic, commercial, or derivative work without explicit permission. This is living, ancestral research—rooted in lineage, not labs.

How African cosmologies and community structures recognized neurodivergent minds as part of the whole—not broken, not cast out.

This segment is part of a larger body of protected and copyrighted research. It draws from oral histories, lived experience, and multilingual archives. The full scope of the work remains unpublished and intentionally reserved from academic extraction or open-source frameworks.

Over the past three years, I’ve spoken with griots from the Fula, Mandinka, Serer, and Wolof branches across my extended family—gathering oral histories, cultural memory, and spiritual knowledge. I used the DSM not to frame the work, but to translate symptoms and behavioral traits into language that could guide questions across generations and dialects. It allowed me to trace neurodivergent patterns that communities already understood—but had never named in clinical terms.

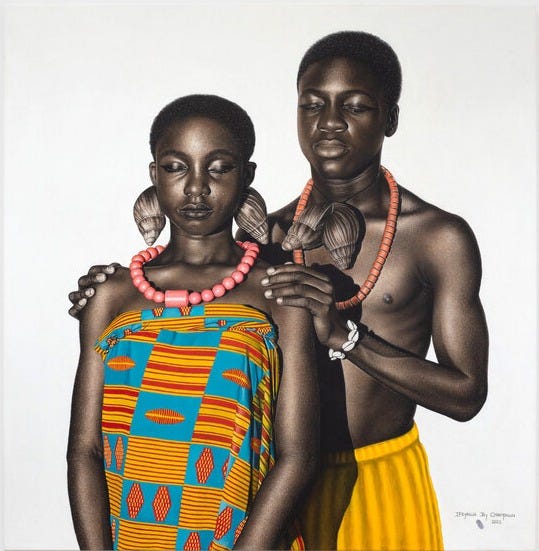

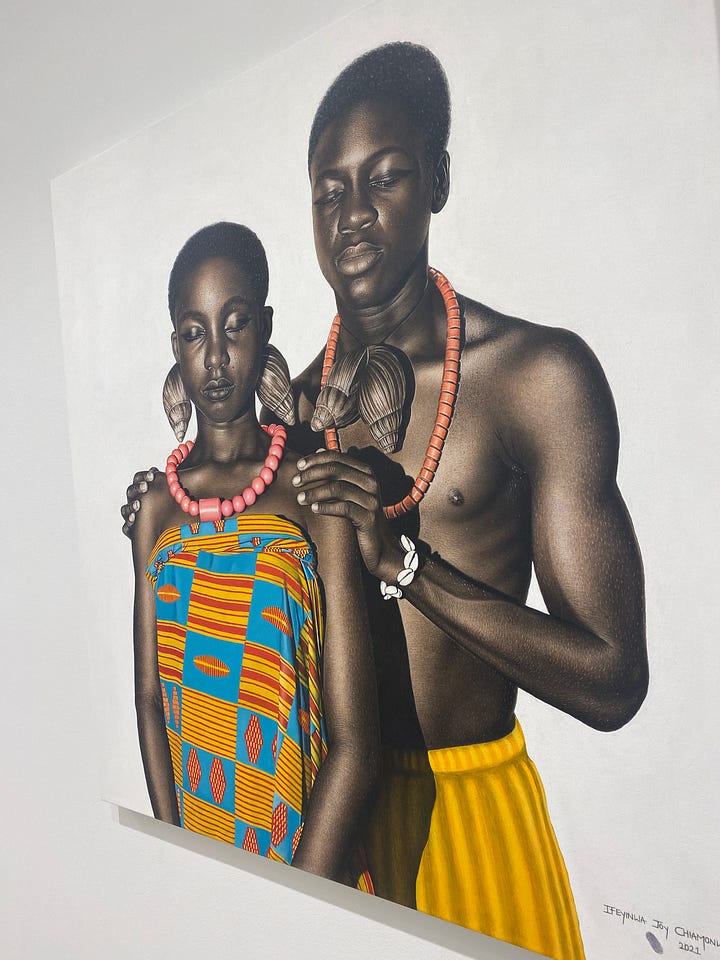

In these precolonial societies, neurodivergent individuals were not seen as broken. They were integrated into communal roles: healers, memory keepers, rhythm holders, energy workers, herbalists, and advisors. Their traits were understood through lived observation—not through pathology. Autism and ADHD were not illnesses; they were specific orientations toward sensory input, attention, language, and time.

This series is not a rewrite of Western theory. It is a remembering—for Black neurodivergent people across the diaspora who’ve been mislabeled, misunderstood, and made to feel like anomalies. We were never broken. We were embedded in structures that understood our function.

“This is cultural research rooted in lineage, not labs—guided by oral historians, spiritualists, and multilingual archives across three regions.” — Lovette Jallow

Whether you are African, Caribbean, or Black American—if this resonates, it’s because you were never outside of it. Our neurodivergence has always existed. In form. In function. In flame.

Neurodivergence Was Spiritual, Not Pathological

“Before the DSM, there was divination. Before labels, there was recognition.” — Lovette Jallow

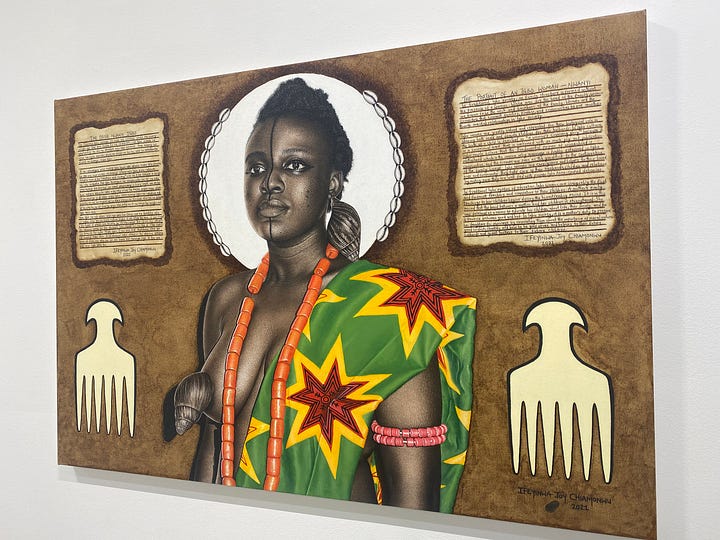

In many precolonial African societies, neurodivergent traits were not medicalized—they were spiritual signposts. A child who didn’t speak for years might be seen as touched by the divine, not broken. An adult with intense focus or unusual routines might be guided by spirit, not a psychiatric manual.

Among the Yoruba, individuals with what would now be called autism were seen as under the care of Obatala—the deity of creation, clarity, and sacred difference. In the Casamance and Senegambian regions, those with heightened sensory awareness often became herbalists, dancers, or dream interpreters. Their neurodivergence didn’t exclude them—it positioned them for unique roles.

Spirituality offered explanations that affirmed instead of erased. Neurodivergence was seen as a function of purpose, not pathology. It was encoded into ritual, belief, and language. The “difference” wasn’t seen as disorder, but as another way the divine showed up in human form.

“Superpowers are not innate. They emerge when difference is supported—not punished.” — Lovette Jallow

This perspective reveals the limits of the Western lens. The DSM pathologizes what ancestors spiritualized. By returning to those frameworks, we recover meaning and reclaim power.

Neurodivergent Griots in West Africa: Storytellers, Memory Keepers, and Living Archives

“We weren’t just rhythm-keepers. We were memory holders, spiritual processors, and the ecosystem’s inner voice.” — Lovette Jallow

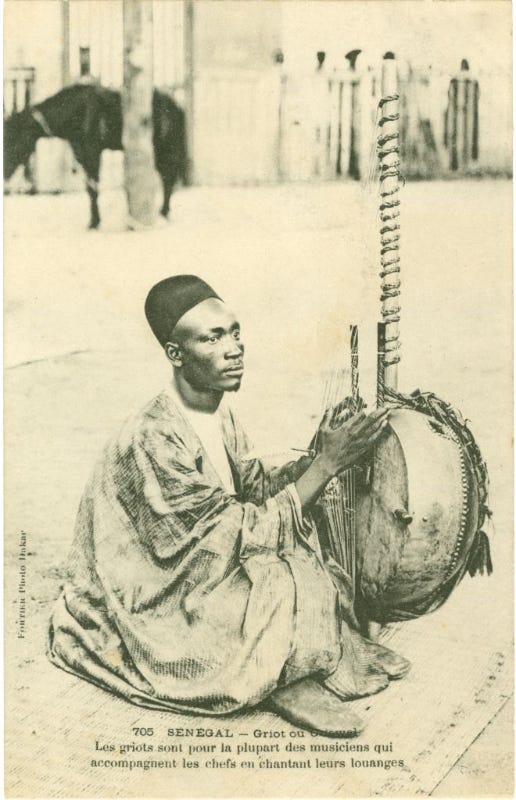

In many West African societies—especially among the Mandinka, Fula, Wolof, Serer, and Yoruba—the griot wasn’t merely a storyteller. They were walking archives. Oral historians with razor-sharp memory and melodic recall, often born into hereditary castes. Their roles weren’t chosen; they were inherited and cultivated from childhood.

I remember being a child, sitting at all family events, marriage ceremonies across Gambia, watching Gewels—especially from our Serer side—step forward to recite entire lineages from memory. They didn’t use notes. They used rhythm. Pattern. Voice. And we all listened, because we knew the drum was about to speak. I grew up watching members of my own family—the Wolof, Fula, and Sarahule branches—each with their own keepers of history, trained from young to carry knowledge that textbooks could never hold.

These griots—Jalis in Mandinka, Gewel in Wolof, Gawlo in Fula—functioned as human hard drives. They stored genealogies, carried political memory, mediated disputes, and blessed unions. Their speech rhythms, melodic storytelling, emotional timing, and sensory depth mirror what today might be labeled as “autistic” or “ADHD” traits: hyperfocus, echolalia, deep empathy, tangential thinking. But back then? It wasn’t pathology—it was purpose.

Speech loops weren’t a flaw—they were tools of retention. Fixation was devotion to detail. Emotional intensity wasn’t disruptive—it was the vehicle of truth. Even those labeled “too blunt” or “too reactive” had a sacred role: the truth-tellers. The ones who wouldn’t lie for kings. The ones who, when seized by something greater, spoke it—damn the consequences.

Their instruments, too, spoke languages of memory. The Kora. The Xalam. The Balafon. The talking drum (Tamo), whose beat could carry messages from village to village. It wasn’t just music—it was infrastructure. It was spiritual language encoded through sound. And it demanded a mind that could recognize patterns, rhythms, nuance. A neurodivergent mind.

You know those who start telling one story, veer into three side stories, drop a proverb or two, then loop it all back in one seamless breath? (whispers: ADHD inattentive). Those were our griots. The scenic storytellers. The ones who annoyed you, then blew your mind. The ones who remembered when the rest of the world forgot.

And as one Mandinka saying goes: “The drum does not lie—it remembers.” So did the griots. And so do we.

Healers, Seers, and the Neurodivergent Spirit Workers

“Not every vision was madness. Not every silence was absence. Some were communion.” — Lovette Jallow

In many West African cultures, neurodivergent individuals often held sacred roles—as herbalists, spiritual mediums, seers, and energy workers. Their sensory sensitivities, pattern-driven thinking, deep empathy, or detachment from the everyday made them ideal vessels for the unseen.

In Casamance, for example, those who were “strange,” who walked at night, who could not sit still in the day but listened well in silence—were called upon when illness struck. In Yoruba cosmology, epileptic seizures weren’t just medical events—they were seen as moments of spiritual possession. What Western science reduced to “episodes,” African traditions interpreted as thresholds between worlds.

Some were Spiritual dancers—those with hyperactive energy, drawn to rhythm and repetitive movement. These weren’t simply physical expressions; they were communal rituals for protection, communication, and healing. Others were herbalists, whose intense interest in textures, smells, and processes made them meticulous medicine makers—like my own grandmother with her hundreds of plants and trees planted.

What the West labels as dysfunction, African societies often held as divine function. These weren’t eccentricities to be fixed but signs to be interpreted. And even when such people made others uncomfortable, they were often placed just outside the village—not cast out, but protected, observed, consulted. Revered.

How Neurodivergence Survived the Transatlantic Slave Trade

“They tried to scatter us, but memory doesn’t drown. Neurodivergence crossed with us.” — Lovette Jallow

The Transatlantic slave trade didn’t just displace bodies. It displaced systems—spiritual, linguistic, ecological, communal. And yet, some things survived. Neurodivergence among them.

Fulani, Mandinka, and other West African groups—many of them with nomadic roots—carried their stories, instincts, rituals, and neurotypes across oceans. Oral traditions that relied on pattern recognition and memory. Herbal systems grounded in sensory precision. Rhythmic, trance-based movement that would later reappear in Afro-Caribbean religions, gospel churches, and coded resistance songs.

Even in the violence of displacement, neurodivergent traits persisted: the child who didn’t speak but understood everything. The elder with unshakable memory. The young adult who couldn’t sit still but always sensed danger first. These were not accidents. These were continuations.

“This is for every Black neurodivergent person who thought they had to disappear to survive. You are not new. You are inherited.” — Lovette Jallow

Among Indigenous American communities, similar reverence for “unusual minds” existed. Totem poles bearing symbols of deities like Obatala, shared rituals with African diasporic faiths—evidence that these traditions met and recognized each other. Neurodivergence was not isolated to one culture; it was honored in many. And through this global kinship, it survived colonization and reasserted itself—often quietly, in kitchens and backyards, among grandmothers and rhythm keepers.

We were not erased. We adapted. And even now, our memory work continues.

Colonialism & the Pathologizing of Black Neurodivergence

“Colonialism didn’t just steal land. It stole our names for things—and gave us theirs.” — Lovette Jallow

When Western colonizers invaded African societies, they didn’t only dismantle political and economic systems—they dismantled cosmologies. The spiritual, linguistic, and communal structures that gave meaning to neurodivergent existence were replaced with medicalization, stigma, and silence.

What was once considered sacred—visions, deep quiet, trance, repetition, intuition—became symptoms. What had been roles became disorders. The griot became “too loud,” the seer “delusional,” the herbalist “superstitious.” Indigenous understandings of difference were intentionally dismantled, replaced with DSM categories that flattened our complexity.

Even our languages suffered. With over 3,000 African languages, there were thousands of words, metaphors, proverbs, and idioms for what the West calls mental illness or neurodivergence. These weren’t just words—they were frameworks. They held nuance. They guided ritual, community care, and inclusion. But when our languages were criminalized and replaced, we lost our mirrors.

And yet—those of us who carry the pattern, the rhythm, the truth-telling—it stayed in our bones. That’s why we can’t fully resonate with the flattening labels. Why many of us were “missed,” “misdiagnosed,” or late-diagnosed. We weren’t missing anything. The world lost the frameworks that used to recognize us.

Reclaiming the Names They Burned

“Why we need new language rooted in ancestral memory.” — Lovette Jallow

We are not rewriting history. We are remembering it with our own mouths.

When Western frameworks failed us, many of us turned inward, then backward—toward oral history, grandmother logic, dreams, song, and silence. In that turning, we remembered. Not perfectly. Not always clearly. But deeply.

We remembered what it meant to be guided by intuition rather than productivity. To be protected, not pathologized. To be part of a communal rhythm where your difference wasn’t an inconvenience—it was a clue. A message. A gift.

To reclaim neurodivergence through an African lens is not about rejecting all modern tools, including diagnosis or medication. It is about restoring choice and context. It is about speaking of ourselves in languages that reflect our complexity, not just our coping.

We must begin to name ourselves again—not in opposition to Western models, but in the full richness of our ancestral memory. Some of us are griots. Some are rhythm-keepers. Some are sky-watchers. Some are herbalists. Some are watchers at the edge of the village, still sensing danger first.

We are all part of the ecology. Our names must reflect that.

This Is Not For Extraction

“For Black neurodivergents first. Not for study. For remembrance.”

— Lovette Jallow

Some knowledge is meant to be carried, not collected. This work is not for everyone. It is not meant to be theorized, mined, or extracted into Western frameworks that once erased us. It is not an invitation for appropriation or comparison, nor a blueprint to flatten culturally specific knowledge into universal claims.

My studies, research and work are not meant to be consumed through the lens of academia or institutional authority. As with all of my writing and intellectual property, this series is protected by copyright. This is not open-source labor for academic repackaging. It is lived, ancestral, and intentionally safeguarded.

It is written first and foremost for Black neurodivergent people—especially those from African lineages—who have felt unrooted, mislabeled, or erased. It is here to remind us that we are not new, not broken, and not alone.

If you are outside the lineage and reading this, read with respect. Read with quiet. Read knowing that not all of this is yours to take. Some of it is sacred. Some of it is closed. Some of it is memory being rebuilt slowly—through voice, not textbooks.

This writing is a bridge, not a map. And every bridge requires care.

I spent years gathering this work—across languages, griot lineages, regions. It took translators, elders, dreams, and silence. This was not academic fieldwork. This was cultural memory recovered under spiritual instruction. It is protected for a reason: some knowledge is sacred. Some of it can’t be cited. It must be remembered through relationship, not research.

We Were Never Gone - A return to ancestral naming

“We are not waiting for permission to exist. We are not new. We are returned.” — Lovette Jallow

This is not the end. It’s a re-entry.

Those of us who have been labeled too intense, too forgetful, too quiet, too honest, too rigid, too chaotic—we were once vital. And we still are. We come from lineages that understood variation in human minds as essential to survival. We were griots, seers, watchers, rhythm-holders, medicine mixers, memory bearers.

This series is not just about reclaiming the past, it’s about honoring the living. About giving language to what many of us have always felt but were never allowed to say: “I make sense in a different framework.”

To be neurodivergent is not to be deficient. It is to carry a rhythm, a fire, an orientation that Western models could not name. But our ancestors did. And we are allowed to speak that language again. To move how we move. To unmask. To remember.

For every Black neurodivergent person searching for themselves outside of Eurocentric systems, this is your confirmation: you were never the problem. The frameworks were too small. You werent seen nor supported.

We were never gone. Just misnamed. And now—we name ourselves. My work is dedicated to you all. And so I continue—toward completion.

© Lovette Jallow. All rights reserved.

This work is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced, republished, excerpted, or used for academic, commercial, or derivative purposes without written permission. This includes institutions, researchers, and media.

We Are Not New

We are your ancestors returning.

We are part of the brain’s ecosystem, not to be pathologized.

We were always here:

the griots,

the storytellers,

the archivists.

The ones who held memory through storms & silence.

The pattern recognizers.

The ones who sensed what others missed.

The truth tellers.

The ones who refused to keep still

when stillness was violence.

We are not waiting for acceptance.

We are remembering.

We are reminding.

We are rewriting.

- Lovette Jallow

If This Resonates

You’ll find more of my essays on breaking intergenerational cycles, Neurodivergence and holding boundaries and reclaiming voice.

Matriarchy vs. Gynarchy: Why Replacing Men Isn’t Liberation | Lovette Jallow

To Book Me for Lectures, Keynotes, and Critical Conversations

I speak internationally on subjects including but not limited to African matriarchal systems, Fulani governance, neurodivergence in pre-colonial societies, anti-racism, intersectionality, and structural violence.

My talks draw from lived experience, academic research, and cultural fluency across seven languages. I do not dilute or perform knowledge for spectacle. I teach from lineage, not theory.

If you're an organization, institution, or collective committed to real change—not checkbox diversity. You can book me for lectures, keynotes, panels, or workshops via: [https://lovettejallow.com/] | [Lovette@Lovettejallow.com]

Who is Lovette Jallow?

Lovette Jallow is one of Scandinavia’s most influential voices on systemic racism, intersectional justice, and human rights. A nine-time award-winning author, keynote speaker, lecturer, and humanitarian, she specializes in neurodiversity, workplace inclusion, and structural policy reform.

As one of the few Black, queer, autistic, ADHD, and Muslim women working at the intersection of human rights, systemic accountability, and corporate transformation, Lovette brings an unmatched perspective rooted in both lived experience and professional expertise. Her work bridges the gap between theory, research, and action, helping organizations move beyond performative diversity efforts toward sustainable, structural change.

She has worked across Sweden, The Gambia, Libya, and Lebanon, tackling institutional racism, legal discrimination, and refugee protection. Her expertise has been sought by global publications like The New York Times, on high-profile legal cases, and by international humanitarian organizations, where she has provided critical insights on racial justice, policy reform, and equity-driven leadership.

Follow Lovette Jallow – DEIB Strategist, Keynote Speaker & Humanitarian:

Website: lovettejallow.com

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/lovettejallow

Instagram: instagram.com/lovettejallow

YouTube: youtube.com/@jallowlovette

Twitter/X: twitter.com/lovettejallow

This was so incredibly beautiful and necessary. Thank you for the time, care, and intention you have brought into helping us recover & reclaim our lost lineages.

Truly brilliant artwork and writing. What a revelation. I have sent this to my west african friend who is struggling to find adequate support for her autistic son here in Sweden.