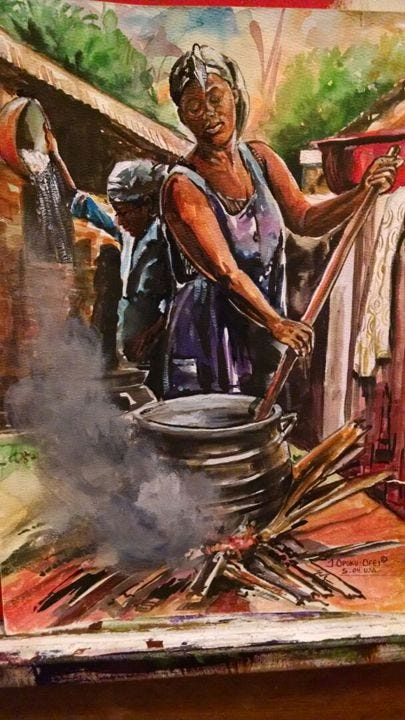

You’re Not Entitled to What You Didn’t Build: Gendered Labor, Food, and Patriarchal Entitlement in Gambian Culture

Why Gambian women are tired of performing unpaid labor masked as hospitality and how patriarchal entitlement hides behind culture, food, and ‘jokes’ about ethnic roles.

What They Call Culture Is Just Entitlement

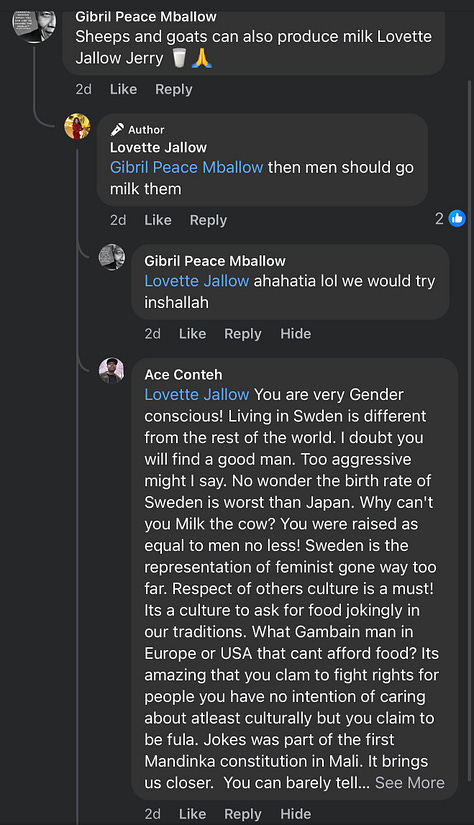

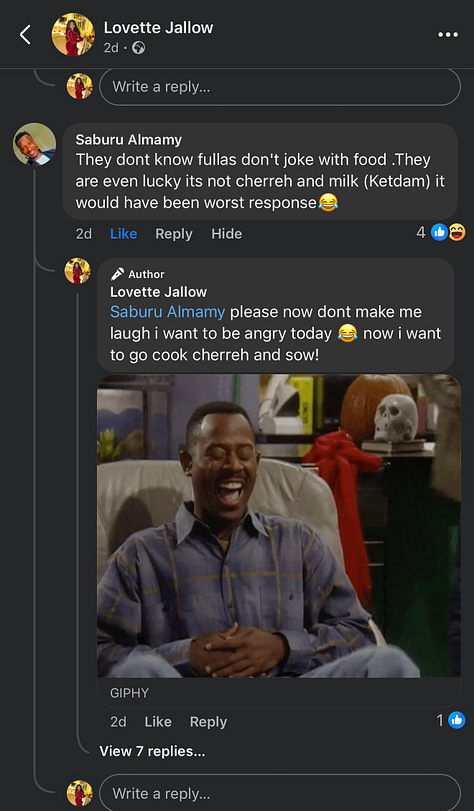

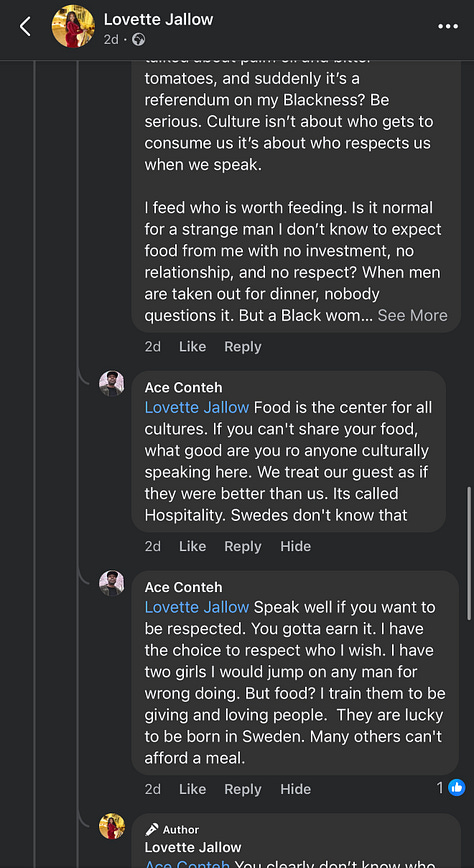

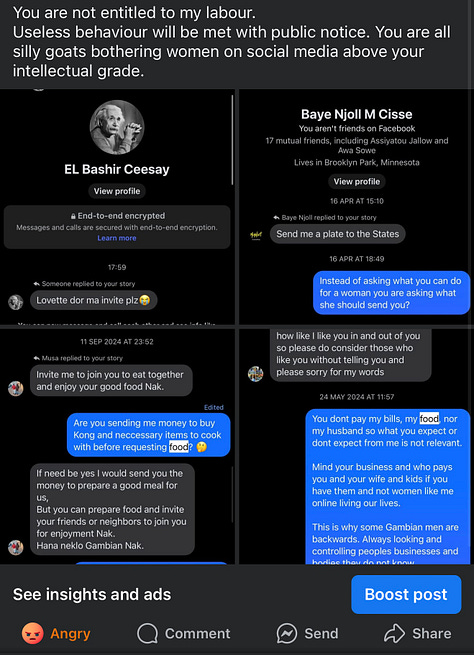

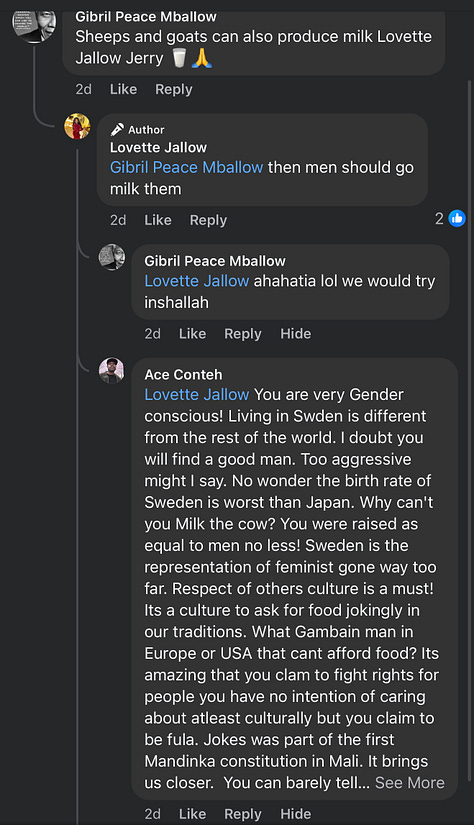

When I post a video of myself cooking with friends, it takes less than 30 minutes before the DMs start. “Send me a plate,” they say. “Domoda invite when?” “Nak, you fulas know how to cook.” Most of them are strangers. Most are Gambian men. And every one of them thinks it’s funny or worse, flattering.

Let’s be clear:

Cooking Gambian food in Sweden is expensive. The ingredients are imported. The labor is mine. The time is unpaid. The joy, sacred. Yet somehow, the moment a woman is seen cooking online, it’s as though we’ve activated a centuries-old button: perform for us, feed us, mother us. It’s not flirtation. It’s not cultural tradition. It’s unpaid, unreciprocated, and expected.

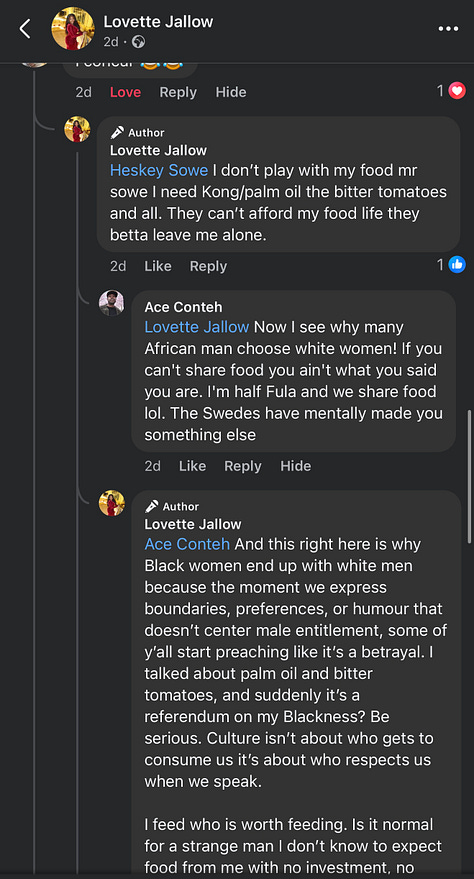

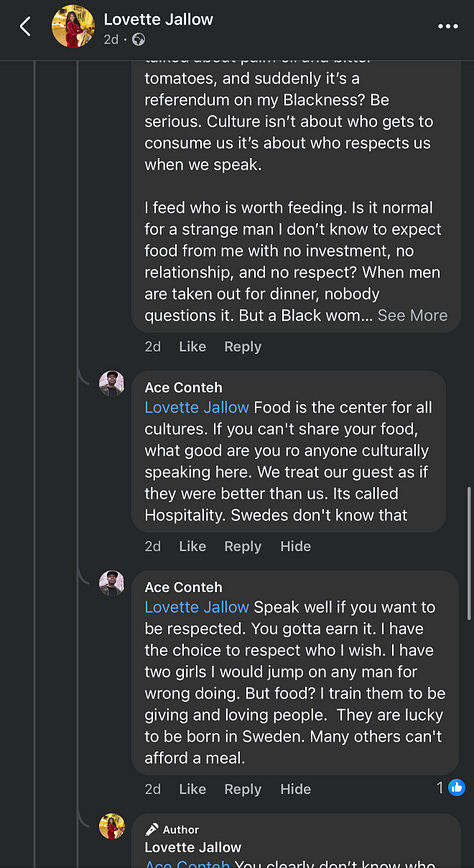

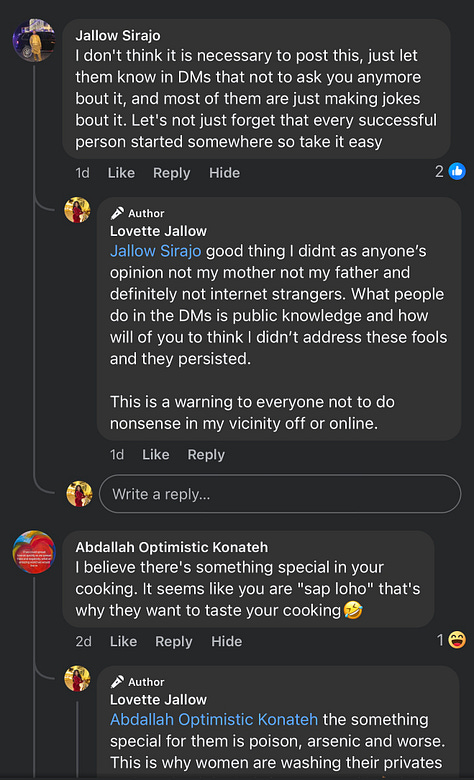

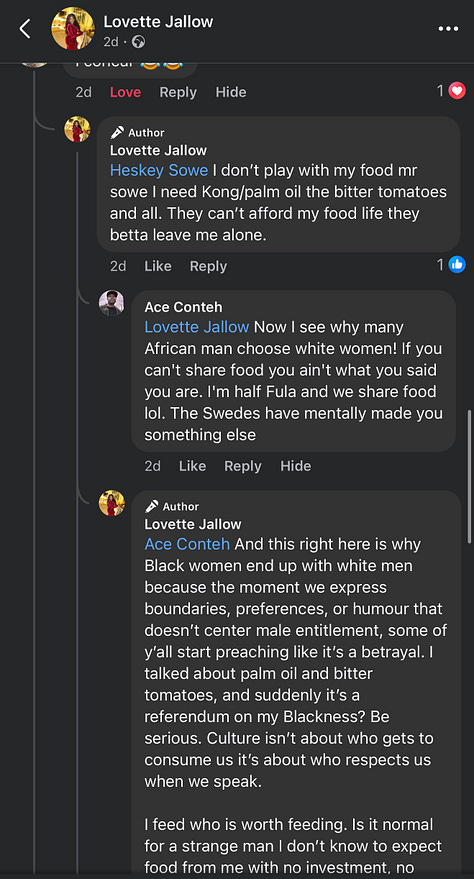

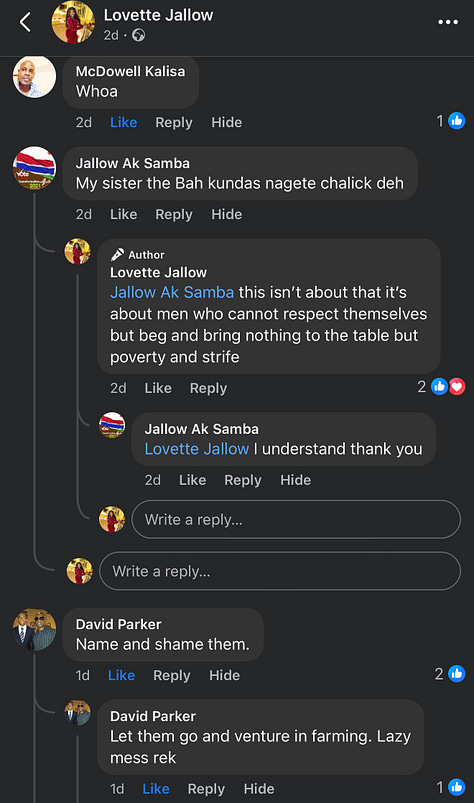

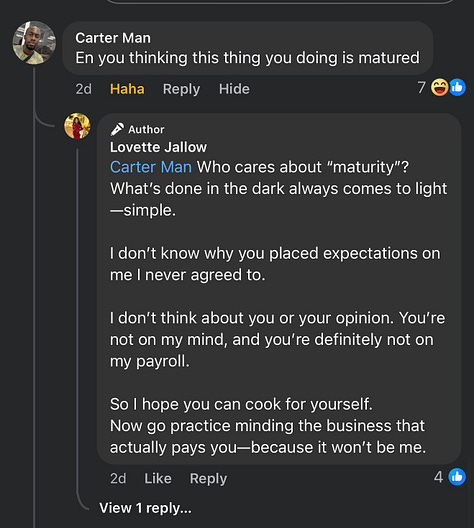

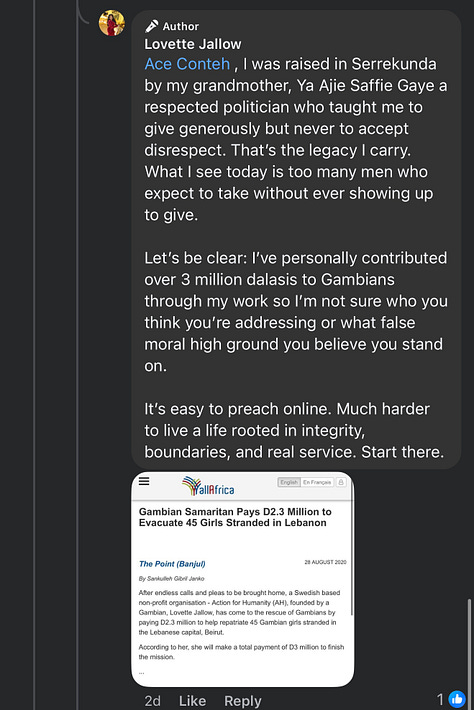

What I said in my posts was not complicated: I don’t cook for men who bring nothing to the table. No investment. No relationship. No respect. But instead of reflection, the backlash came quickly and with it, the usual deflections. I was called un-African. Westernized. Ungrateful.

“Swedes have made you forget who you are,” one said.

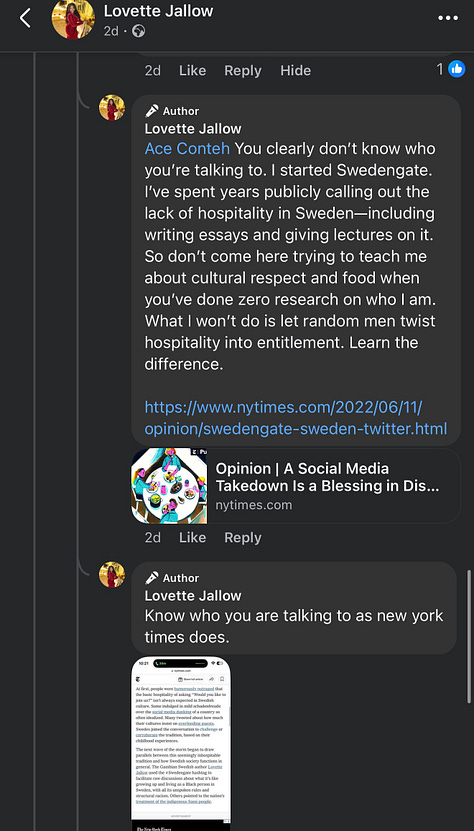

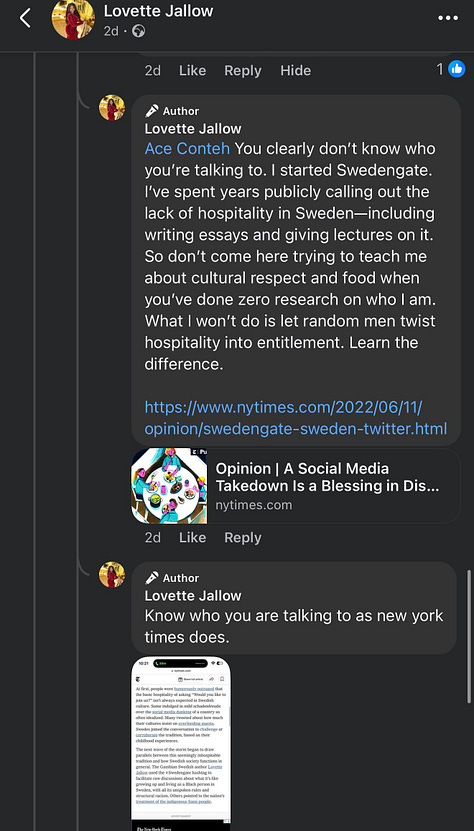

Which is ironic, considering I was the one that started and coined Swedengate and went viral for it. But Swedengate was about children being denied food while already inside someone’s home. That’s not the same as grown men 35, 40, 50 years old demanding access to a woman’s time, labor, and kitchen as though they’re owed something. These are not children. They are not guests. And they will not be infantilized to excuse their entitlement.

But who am I really supposed to be? A kitchen-bound ghost of servitude? An unpaid caterer in the name of culture?

If you’re new to my work or curious about the full Swedengate critique, you can read my essay here:

When Gendered Labor Is Masked as Hospitality

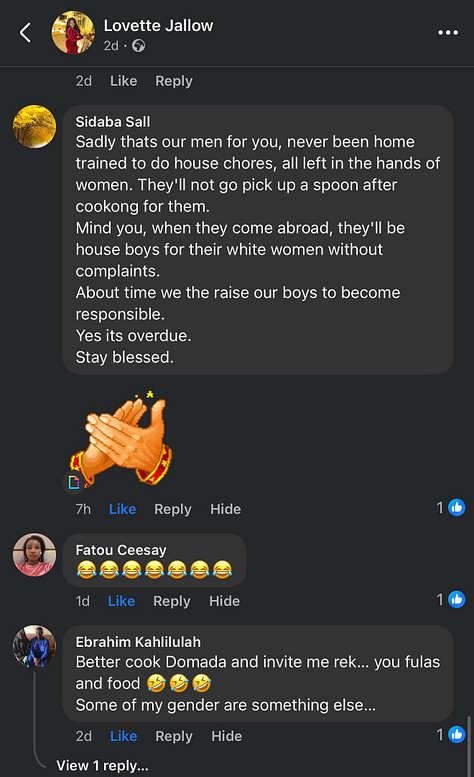

Gambian culture, like many West African cultures, prides itself on hospitality. We feed people. We host. We give. But here’s what doesn’t get discussed: the labor behind that hospitality has always been gendered—and largely invisible. Women shop. Women cook. Women serve. Men arrive with jokes and appetites, and leave with full bellies and empty hands.

This is not generosity. It’s extraction.

The expectation that Gambian women will perform this labor without acknowledgement or reciprocity has been normalized under the guise of culture but it is patriarchy, plain and simple. The moment a woman sets boundaries, the accusations fly: you’re selfish, you’re not African enough, you’ve become too Western. But boundaries aren’t Western. They’re survival.

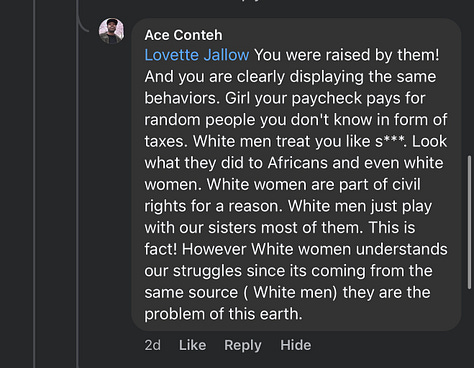

And the labor many men refuse to do in our homes—washing dishes, cooking meals, preparing food for guests they perform without hesitation abroad for white women. One man even said this is why Black men choose white women. That alone tells you everything: their view of women, in general, is transactional. They reject boundaries from Black women but have no issue becoming houseboys for white wives in Europe—yet claim exhaustion the moment they land in Gambia

My labor is not transactional, and no one is entitled to it. I don’t perform domesticity on demand, and who anyone chooses to partner with is not my concern. Arguing otherwise is flawed from the start—it confuses entitlement with culture and erases the autonomy of the women you're speaking over.

They’ll Call You Western While Recreating Colonial Hierarchies at Home

Before we move on to the financial and emotional cost of feeding people who don’t feed us, let’s talk about something else I’ve noticed in the backlash:

The men who criticize me for being ‘too Western’ are often the same ones who partner with white women and then re-perform colonial dynamics under the guise of ‘culture.’

They don’t see the contradiction.

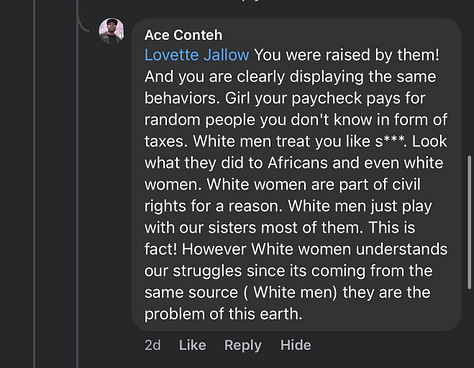

They accuse me of being “raised in the West,” despite the fact that I was raised in Gambia, by Gambian elders, in matriarchal traditions many of them were too entitled to fully understand. They flatten identity and erase the complexity of ethnic dynamics within the country. They see Fula structure, emotional independence, or refusal to submit as Western contamination, rather than what it is: a lineage of matriarchal governance they were never expected to carry.

But let’s be honest: some of these same men are quick to perform labor and compliance in their relationships with white women abroad. They become helpful. Polite. Accommodating. Suddenly, the man who couldn’t wash a spoon in Gambia is meal-prepping and cleaning in silence—because whiteness is still associated with consequence, while Black women are associated with forgiveness and sacrifice.

Yet the moment a Black Gambian woman is seen thriving with a partner especially one who treats her well and isn’t Gambian, or maybe isn’t even Black the same men are enraged.

They expect loyalty without reciprocity, respect without effort, and cultural performance without comprehension.

They want the benefits of our labor, our culture, our food, our lineage - But not our voice, our boundaries, or our joy.

This is what happens when patriarchy intersects with internalized colonialism: Men feel entitled to labor from women they refuse to understand and outraged by love that doesn’t center them.

This is why I don’t judge anyone who finds love with another consenting adult—whether monogamous, poly, or anything else. People deserve to choose the version of peace that makes sense for their life, not the one others find most palatable. And more often than not, it’s the unhealed who project their discomfort onto someone else’s joy.

If that resonates, I’ve written more about this in a separate essay reflecting on Nikki Giovanni, intimacy, and how interracial relationships are often policed not from principle, but from entitlement:

Ethnic Jokes Are Just Patriarchy in Disguise

The comments weren’t just lazy, they were ethnically coded. “You Fulas know how to cook,” one man said. “You should be feeding me.” Another joked, “Sisays always want food.” This isn’t harmless banter it’s patriarchal entitlement dressed up as cultural humor.

In reality, these jokes reinforce hierarchies:

Fula women are expected to be nurturing and generous, no matter the cost. Certain surnames become punchlines for male dependency.

Asking for food becomes shorthand for access to women’s emotional and physical labor.

Ethnicity is being weaponized to reassert gendered expectations that Gambian women should serve without questioning. And when we do speak up, we are told our Blackness, our Africanness, our womanhood is invalid.

The Cost of Feeding People Who Don’t Feed You

To cook Domoda from scratch in Sweden is a financial investment. Bitter tomatoes. Kong. Proper palm oil. Shipments that cost triple what they do in Gambia. Every spoonful comes with labor, expense, intention. So when a man who’s done nothing for me—nothing—slides into my inbox to ask for food, that’s not a joke. That’s structural disrespect.

And yet, when I set a boundary, it’s not heard. Instead, it becomes a referendum on my values. I’m too outspoken. I’m not respectful. I’m too “Western.” But ask yourself this: why is it that women setting boundaries is viewed as betrayal, while men extracting from us is viewed as cultural?

Culture Is Not an Excuse for Entitlement

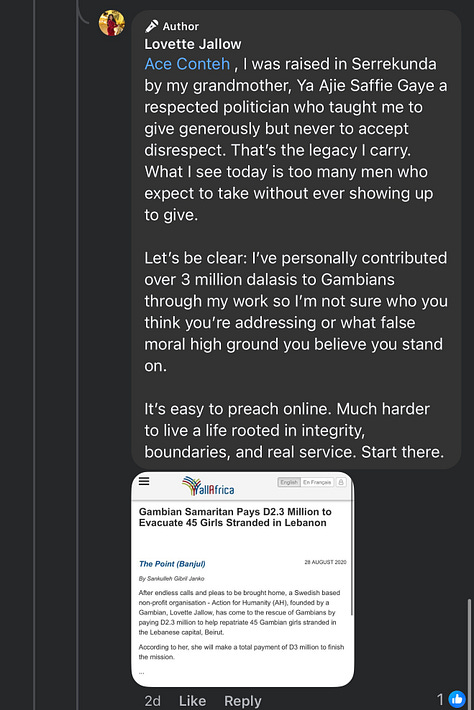

I was raised in Serrekunda by a woman who gave to the people and taught me to expect respect. I’ve spent years doing humanitarian work, feeding communities, evacuating Gambian girls from Lebanon, building safety for those no one else would. That’s culture. That’s dignity. That’s service rooted in boundaries not submission.

So no, I’m not flattered by your request for Domoda.

I’m not interested in being consumed for your entertainment.

I don’t feed men who arrive empty-handed. And no, I don’t need your cultural lectures about sharing food especially from those who think my labor is their birthright.

Culture isn’t who consumes us. It’s who respects us when we Speak

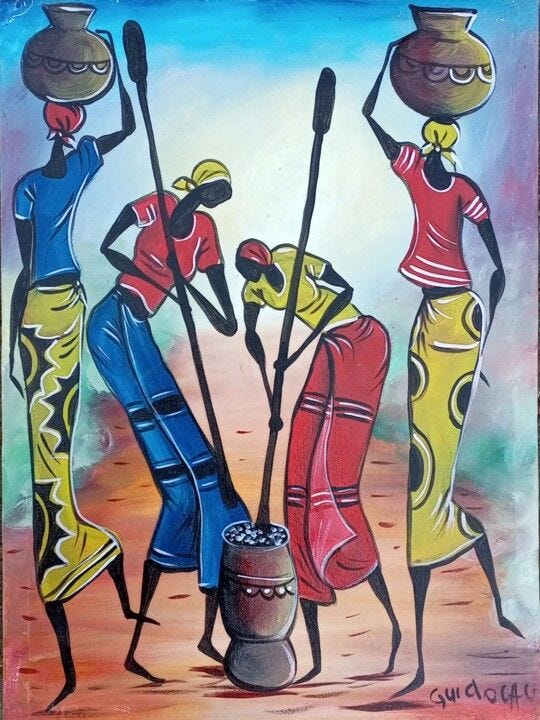

Here is a video of the revipe and cooking video i made cooking Gambian Domoda (peanut stew). If anyone feels hungry they can always cook.

© Lovette Jallow. All rights reserved.

This work is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced, republished, excerpted, or used for academic, commercial, or derivative purposes without written permission. This includes institutions, researchers, and media.

If This Resonates

You’ll find more of my essays on breaking intergenerational cycles, Neurodivergence and holding boundaries and reclaiming voice.

Matriarchy vs. Gynarchy: Why Replacing Men Isn’t Liberation | Lovette Jallow

To Book Me for Lectures, Keynotes, and Critical Conversations

I speak internationally on subjects including but not limited to African matriarchal systems, Fulani governance, neurodivergence in pre-colonial societies, anti-racism, intersectionality, and structural violence.

My talks draw from lived experience, academic research, and cultural fluency across seven languages. I do not dilute or perform knowledge for spectacle. I teach from lineage, not theory.

If you're an organization, institution, or collective committed to real change—not checkbox diversity. You can book me for lectures, keynotes, panels, or workshops via: [https://lovettejallow.com/] | [Lovette@Lovettejallow.com]

Who is Lovette Jallow?

Lovette Jallow is one of Scandinavia’s most influential voices on systemic racism, intersectional justice, and human rights. A nine-time award-winning author, keynote speaker, lecturer, and humanitarian, she specializes in neurodiversity, workplace inclusion, and structural policy reform.

As one of the few Black, queer, autistic, ADHD, and Muslim women working at the intersection of human rights, systemic accountability, and corporate transformation, Lovette brings an unmatched perspective rooted in both lived experience and professional expertise. Her work bridges the gap between theory, research, and action, helping organizations move beyond performative diversity efforts toward sustainable, structural change.

She has worked across Sweden, The Gambia, Libya, and Lebanon, tackling institutional racism, legal discrimination, and refugee protection. Her expertise has been sought by global publications like The New York Times, on high-profile legal cases, and by international humanitarian organizations, where she has provided critical insights on racial justice, policy reform, and equity-driven leadership.

Follow Lovette Jallow – DEIB Strategist, Keynote Speaker & Humanitarian:

Website: lovettejallow.com

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/lovettejallow

Instagram: instagram.com/lovettejallow

YouTube: youtube.com/@jallowlovette

Twitter/X: twitter.com/lovettejallow

Eyyyy that last comment of you was fire!! It had me gasp in respect! Ah.

All that lacked was a drum roll after that. Boom!

You are so eloquent and may I say, walking your talk. So right.

Some men on dating sites think it’s sexy to ask me to cook for them on a first date. Are you kidding me? I delete them without reply. Nobody has time for another deadbeat open mouth only taking and taking. But I’m white so its different than what you are talking about. Just to say: some men just expect us (women) to mother them. I already have three soms and a dog. That’s enough.

As a gambian, you putting into words of what i’ve found disturbing about some aspects of Teranga. It’s also the fact that it’s not reciprocal - men just take and take.