When Men Protect Boys Instead of Naming Harm, They Don’t Disrupt Violence—They Preserve It

How Netflix’s Adolescence Exposes the Incel Pipeline, and Why Fragile Men Can’t Lead Anyone Out of It

Adolescence, Incels, and the Men Who Think They're Helping

There’s a quote I’ve returned to more than once:

“Men are afraid women will laugh at them. Women are afraid men will kill them.”

It lands differently when you’re a Black woman and sharper still when you’re autistic. And it resonates like a scream behind glass when you watch Adolescence—the Netflix docuseries that chronicles the chilling duality of a teenage boy who commits an unthinkable act of violence, and the disturbing reluctance of society to believe he could be capable of it.

This quote resurfaces for a reason:

And it resonates like a scream behind glass when you watch Adolescence—Netflix’s docuseries that examines the chilling duality of a teenage boy who commits an unthinkable act of violence, and the disturbing reluctance of society to believe he could be capable of it.

This quote resurfaces for a reason:

It encapsulates the asymmetry in threat perception.

Boys are often taught that being humiliated is worse than being violent.

Adolescence quietly exposes how early that male entitlement begins—and how rarely it’s interrupted. We are always taught to doubt the danger in men.

And then, when the danger shows up with a smile, we’re told we’re imagining it.

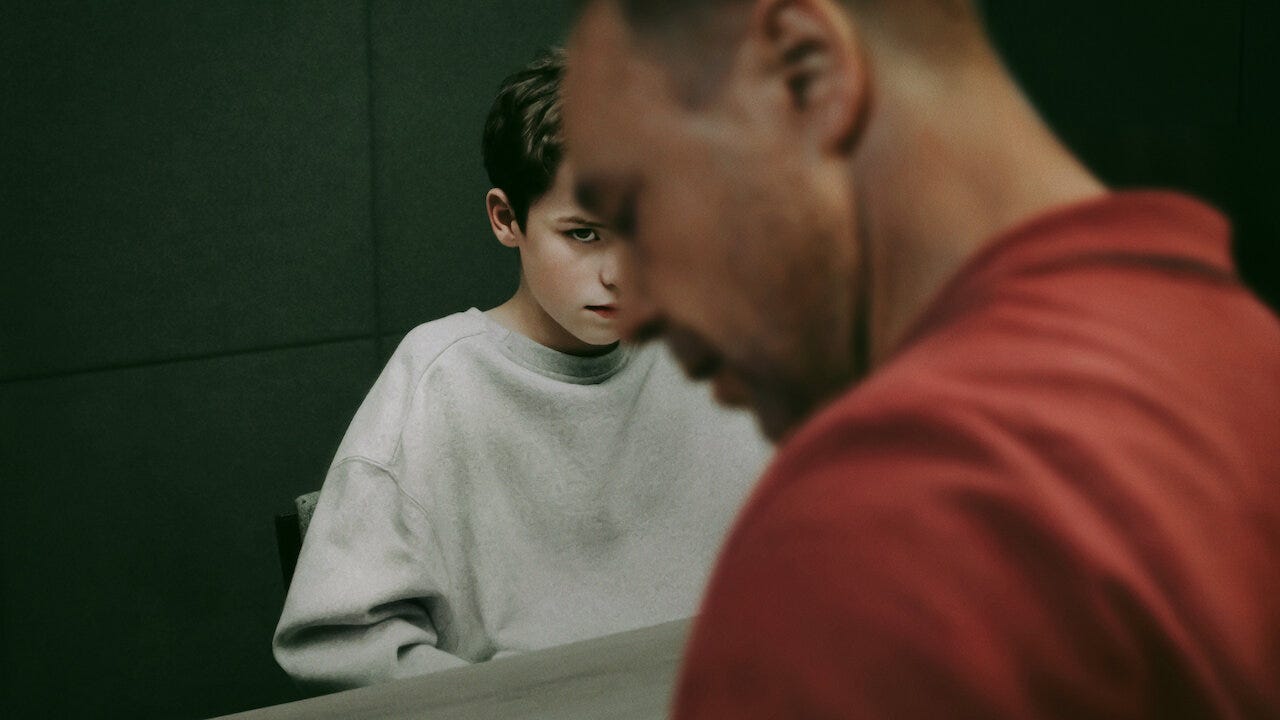

Because this boy doesn’t look dangerous.

He’s young. Soft-spoken. At times, almost childlike.

So viewers hesitate. They search for excuses, for context, for anything that might preserve the illusion of his innocence.

And then we meet the father—and everything becomes clearer.

The boy’s “split personality” doesn’t emerge from a vacuum.

His father walks through the house like he owns every atom of space. Loud. Unchecked. Expected to be obeyed.

You begin to see the blueprint. The modeling. The silence.

The boy didn’t invent violence. He absorbed it.

And the father stood by him—protective, unmoved, unwilling to name what was unfolding right in front of him.

That’s what Adolescence reveals if you’re paying attention.

Not just the violence itself, but the architecture around it.

Fathers who confuse loyalty with denial.

Men who treat accountability like betrayal.

Households where emotional avoidance is inherited just as much as rage—where intergenerational harm lives in silence.

Many viewers missed it.

They clung to the boy’s innocence even after the evidence.

They hesitated, made excuses, softened the story in their minds—because the alternative required confronting something harder:

That men can love their sons, protect their sons, and still raise them to harm others.

That’s the discomfort Adolescence holds us in.

And it’s the same discomfort that shows up every time a man claims to “help” while reenacting the very harm he says he’s addressing.

Why Society Refuses to Believe Some Boys Are Dangerous

What Adolescence lays bare is the cultural refusal to reckon with what many women and girls already know:

Some boys are dangerous.

Not because they’re evil or broken, but because they are socialized to be entitled, unaccountable, and emotionally volatile—with no consequences.

Even after Adolescence aired, viewers asked whether the boy was “really guilty.” Even after footage, interviews, and emotional manipulation laid bare the signs—people still hesitated.

Why?

Because believing he did it requires believing boys like him—quiet, pale, polite, sometimes even pitiful—are capable of harm.

That they don’t need to look monstrous to do monstrous things.

It’s easier to believe girls are dramatic than to believe boys are dangerous.

It’s easier to protect male potential than to mourn the girls they harm.

It’s easier to pathologize women’s reactions than to interrogate men’s actions.

That’s the discomfort.

That’s the tension the series invites you to sit with.

And many still looked away.

Because we are culturally conditioned to doubt a boy's capacity for violence—especially when he’s young, soft-spoken, or comes from a “good home.”

When Men Say They’re Helping But Make Themselves the Victim

After I published my original Substack essay on incel violence and the systems that enable it, most responses were civil and thoughtful.

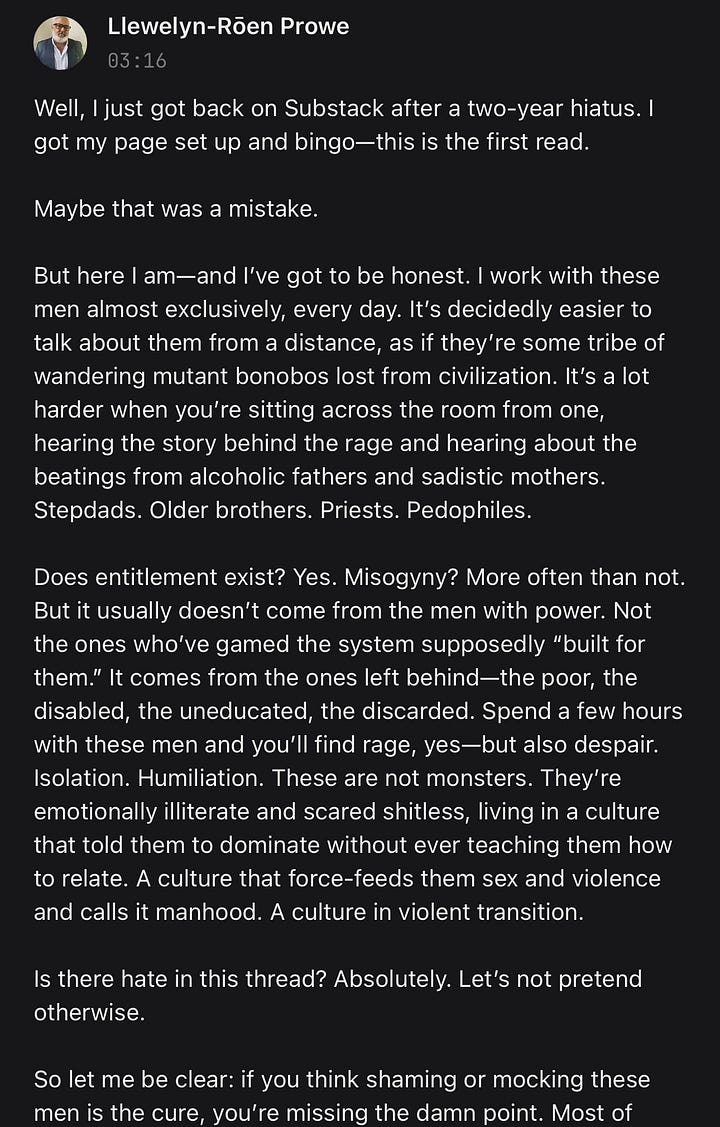

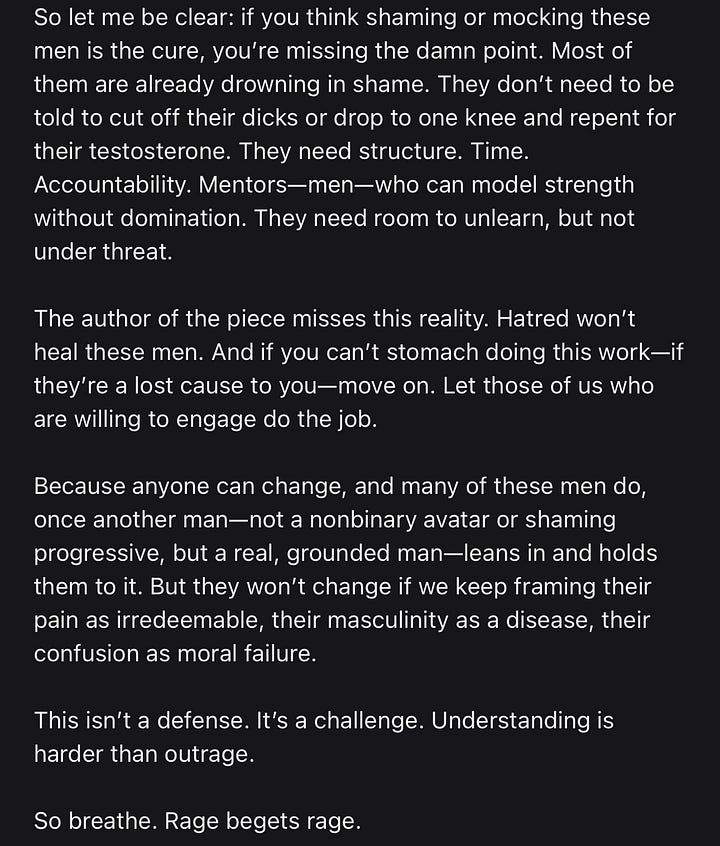

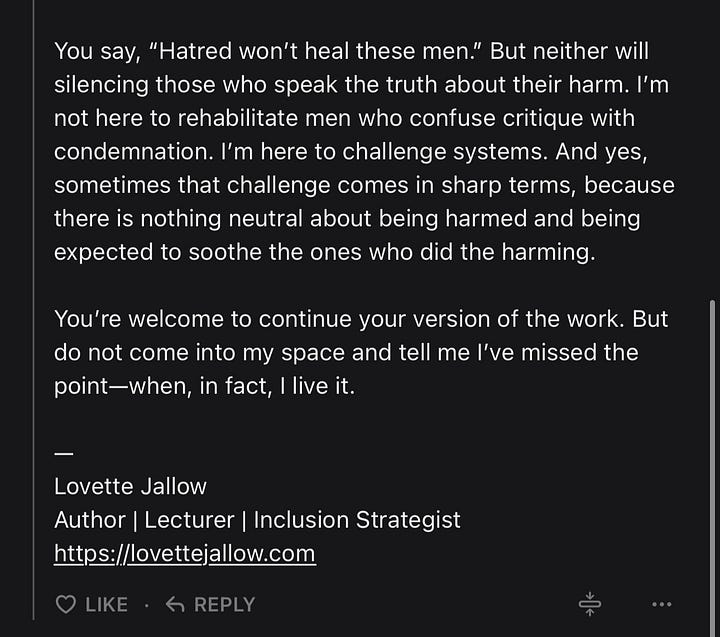

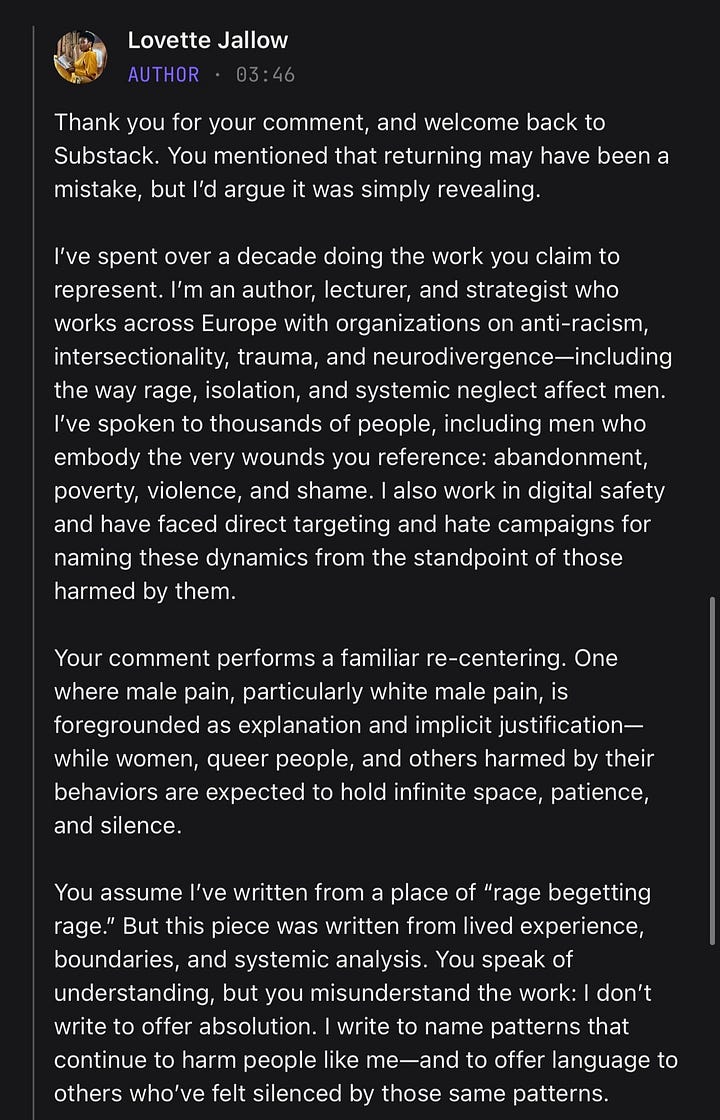

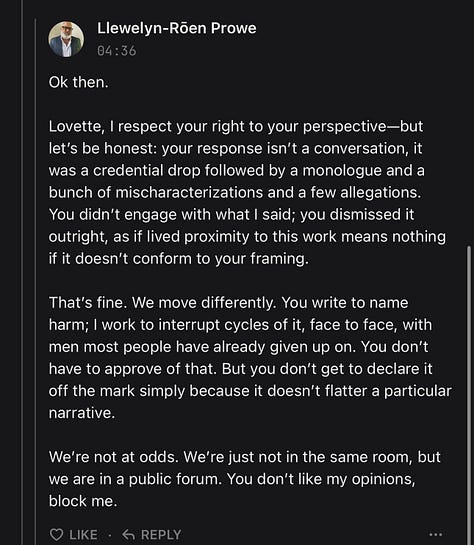

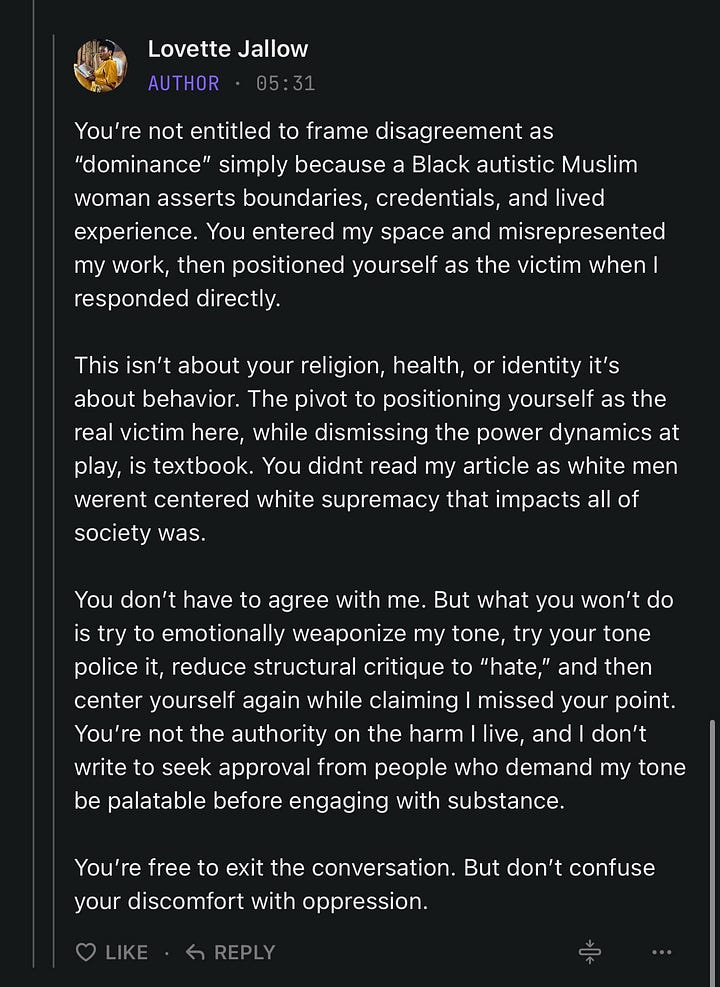

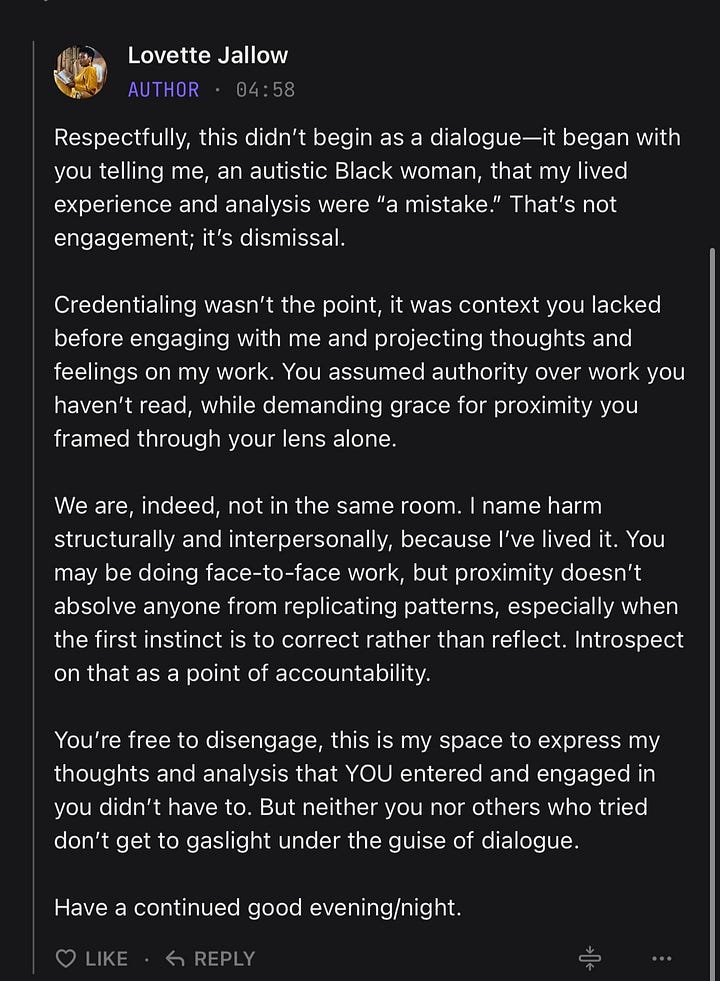

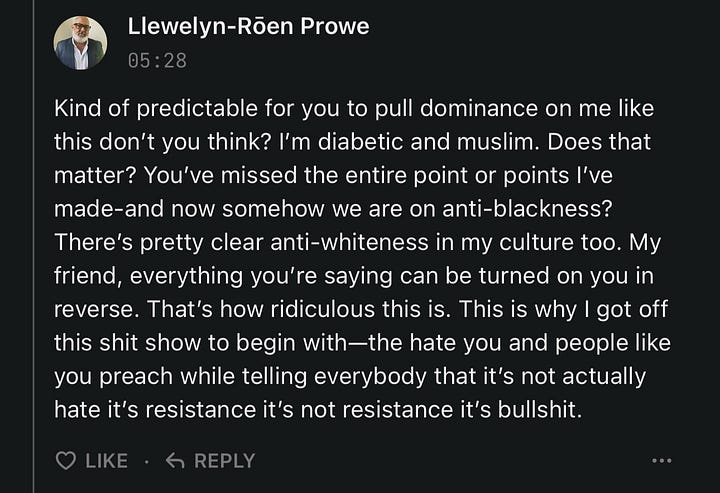

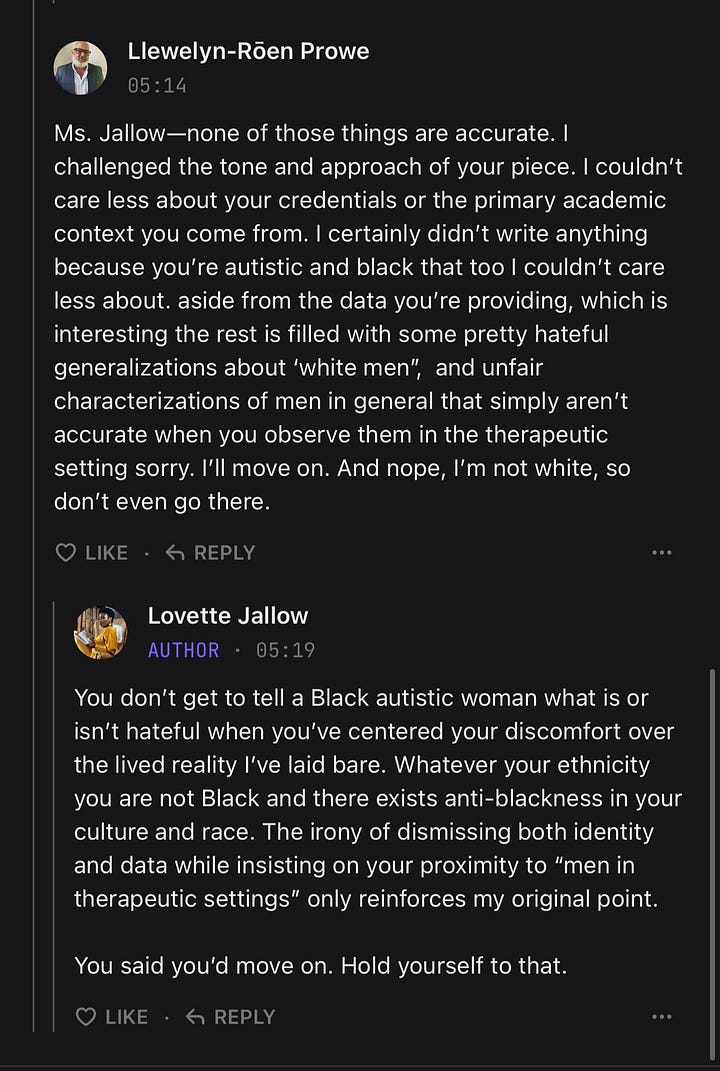

Then a man—Llewellyn-Roën Prowe—entered the thread with authority, positioning himself as someone with insider insight. He identified as a mental health professional who “works with these men.” But what followed wasn’t insight. It was a masterclass in deflection, wounded ego, and digital fixation.

He didn’t engage my essay with respect or curiosity.

He arrived with correction and control.

He described my work as “a mistake.”

He used the phrase “reverse racism.”

He ignored the content and fixated on my tone.

He demanded to be heard—then accused me of emotional harm when I responded.

He even claimed the women in the comments were “angry.”

It followed a now-predictable cycle:

Step 1: Enter a space authored by a Black woman and immediately challenge her expertise.

Step 2: Shift the focus from structural critique to personal offense.

Step 3: Recast boundaries as aggression and critique as “hate.”

Step 4: When the community doesn’t rally behind you—maybe even laughs at your behavior—you perform righteous victimhood.

Step 5: Flounce. Delete. Return. Flounce again.

Over the course of 24 hours, Llewellyn replied, deleted, re-replied, and created three new Substack accounts. His exit was never final.

He lingered like a specter—always monitoring, always re-entering.

His behavior didn’t read like disagreement.

It read like digital obsession.

It read like entitlement—to my labor, my tone, and my platform.

He did not offer insight. He centered his ego.

He did not engage the issue. He made himself the issue.

He did not hold space. He demanded it.

He called me “dominant” for protecting my time.

He weaponized my Blackness and my autism as both reference and rebuke—treating my identity as performance, my expertise as threat, and my boundaries as violence.

Despite repeatedly announcing his exit, he resurfaced across platforms—monitoring, commenting, and trying to reinsert himself into the conversation.

All while claiming to be someone who “guides boys out of incelhood.” How, exactly?

Llewellyn is not unlike the father in Adolescence—not physically, not contextually—but structurally. Both respond to harm not with confrontation, but with fragility. Both shield instead of reflect.

Both treat emotional challenge as an attack on their authority, not a call to grow.

I’ll let the screenshots and videos speak for themselves. This wasn’t disagreement. It was a performance. A digital reenactment of the very dynamic Adolescence put on screen.

Incels Are Not an Internet Problem—They Are an Inheritance

We love to treat incels like they’re fringe.

Like they exist in basements or Reddit threads, disconnected from “normal” men.

But that’s dishonest.

Incel ideology is just patriarchy in a hoodie.

It’s entitlement, weaponized loneliness, and socialized misogyny—expressed through digital language.

It’s emotional underdevelopment, rebranded as resistance.

And many men outside those forums still carry its DNA.

So what happens when the therapists, coaches, and fathers expected to intervene bring the same fragility, projection, and entitlement they claim to be healing?

What happens when those men rebrand their harm as help?

You can’t walk someone out of a mindset you’ve never truly left.

You can’t guide boys into accountability if you interpret boundaries as disrespect. Whether it’s in a therapy room, a classroom, or a comment thread—if you’re centering your own comfort, you’re not dismantling patriarchy.

You’re reinforcing it.

And if the people tasked with helping boys unlearn toxic masculinity can’t even handle critique—especially from a Black autistic woman with both lived and professional expertise—how can they possibly model emotional maturity?

The Performance of Care: How Fragile Men Weaponize Clinical Language

Men like my Substack stalker don’t enter conversations like these to dismantle systems. They enter to defend themselves from what they might have to confront if they actually looked closer.

It’s easy to analyze harm from a distance.

Harder when the mirror is handed to you.

Harder still when that mirror is held up by a Black woman who won’t shrink.

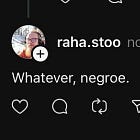

It never takes long on these platforms before someone, somewhere, decides that a Black woman—especially one who is direct, informed, and unbothered—needs to be “put in her place.”

There’s a particular tone they use. A performance of civility that masks entitlement. I can usually sense it from the first few words: the simmering discomfort with my confidence, the barely veiled condescension, the way they circle me—waiting for a misstep.

This time, it came dressed as clinical authority.

Llewellyn didn’t offer thoughtful engagement.

He didn’t ask questions, seek context, or contribute perspective.

Instead, he dismissed my work as “a mistake,” labeled my tone “contemptuous,” and began tone-policing me under my own essay.

Where Eddie—the father in Adolescence—walks through the house as if entitled to silence, Llewellyn walks into digital spaces expecting obedience.

And collapses when he doesn’t get it.

When I refused to make myself smaller, he escalated—quickly and obsessively.

He monitored my posts across platforms. He replied, deleted, re-entered, and created new accounts.

He claimed harm while causing disruption. He expected deference while refusing reflection.

His version of “clinical insight” looked a lot like emotional projection dressed in therapeutic language.

This isn’t professional behavior. It’s obsession disguised as dialogue. And I’ve seen it before. When Black women speak with clarity and command, someone always shows up convinced their discomfort should become our burden.

Helping Boys Means Holding Men Accountable First

You Can’t Guide Boys Out of Misogyny If You Protect the Men Who Shaped Them

Adolescence doesn’t just show us how a boy became dangerous. It shows us how the men around him failed to intervene—how they dismissed, overlooked, or outright enabled what was in plain sight.

Not because they couldn’t see it, but because seeing it would require doing something.

That’s what Llewellyn represents.

Llewellyn is not the boy. He’s the father.

Not in role—but in function.

Emotionally absent, yet reactive.

Protective of an image.

Unwilling to confront what’s in front of him—because it would require him to change.

His resistance grew louder the firmer I stood.

His defensiveness intensified every time I refused to coddle his ego.

The more I named the pattern, the more he made it personal.

And that’s the point.

If these are the men who claim to lead boys out of misogyny and violence—

Men who cannot tolerate critique from a Black autistic woman without spiraling—

Then how can we trust they’re doing the real work?

Allyship that crumbles under scrutiny was never allyship.

It was a performance.

It’s the same dynamic we see in all-white rooms trying to “do” diversity or anti-racism—

Without input from the people most impacted.

Many of whom are experts in their own lived experience.

This work is not a solo performance.

It’s meant to be collaborative.

But I personally will not coddle male ego.

I don’t work through emotional entanglement.

My approach is grounded: cognitive empathy, and—if necessary—compassionate empathy.

That’s it.

You cannot sway me with performance or projection.

I know where I begin and where I end.

I have no desire to enmesh with anyone.

The Limits of POC Solidarity—Especially for Black Women Naming Harm

Not All POC Experiences Protect Black Women

Llewellyn repeatedly referenced his racial and ethnic background as a defense—insisting that because he wasn’t white, he couldn’t possibly be participating in harm.

But anti-Blackness is not exclusive to whiteness.

And proximity to marginalization doesn’t grant you immunity from perpetuating it.

The boy in Adolescence is white.

And yes—whiteness shaped how he was treated: by the justice system, by media, by the audience.

But these kinds of crimes are not confined to whiteness.

Violence, entitlement, and patriarchal control exist across cultures.

The difference lies in how we respond to them.

In families where Black girls are the victims, that same empathy—the same “how could he?” energy—rarely arrives.Instead, there is adultification. There is silence. There is less urgency, less protection, and less institutional care.

When violence intersects with anti-Blackness, Black girls become footnotes in their own trauma.

They’re rendered more culpable, less innocent, and more disposable in the eyes of systems that were never built to protect them.

The boy in Adolescence is from a white family.

But we’ve seen this story in other forms: in Asian families, Arab families, African families. It is not race-neutral. It is systemically layered.

Llewellyn’s attempt to shield himself from critique by invoking his racial identity is part of that same pattern. Because being racialized does not mean you’re in solidarity with Black women—Especially when we’re naming harm.

Black women are often expected to absorb harm in silence, even within communities of color. Especially when we’re the ones drawing the line.

Terms like “POC” or “BAME” are not protective when used to erase the specificity of anti-Black misogyny.

Let’s be clear: Racial solidarity that requires Black women to shrink is not solidarity. It’s strategy.

And I will not play along.

This Is Why We Name Patriachal harm. This Is Why We Don’t Back Down.

I don’t write for applause.

I write because the pattern is so familiar, it’s almost boring in its predictability:

Boys who weaponize silence.

Men who call critique “attack.”

Therapists who expect deference, not dialogue.

Commenters who treat boundaries as violence.

Readers who treat survival as spectacle.

Llewellyn may have deleted his account— But he has created three more and counting in under 24 hours. He came to dominate.

When that failed, he rebranded it as harm.

That’s not neutrality.

That’s a pattern.

And if you’re paying attention, it’s everywhere.

Because the danger isn’t always loud.

Sometimes, it shows up with credentials.

It speaks in therapeutic language.

And it asks the person naming harm to be quieter.

Want to read more on incel ideology, patriarchy, and male fragility?

Here are my other essays unpacking misogyny, structural violence, and what happens when society protects male potential at everyone else’s expense.

Who is Lovette Jallow?

Lovette Jallow is one of Scandinavia’s most influential voices on systemic racism, intersectional justice, and human rights. A nine-time award-winning author, keynote speaker, lecturer, and humanitarian, she specializes in neurodiversity, workplace inclusion, and structural policy reform.

As one of the few Black, queer, autistic, ADHD, and Muslim women working at the intersection of human rights, systemic accountability, and corporate transformation, Lovette brings an unmatched perspective rooted in both lived experience and professional expertise. Her work bridges the gap between theory, research, and action, helping organizations move beyond performative diversity efforts toward sustainable, structural change.

She has worked across Sweden, The Gambia, Libya, and Lebanon, tackling institutional racism, legal discrimination, and refugee protection. Her expertise has been sought by global publications like The New York Times, on high-profile legal cases, and by international humanitarian organizations, where she has provided critical insights on racial justice, policy reform, and equity-driven leadership.

As the founder of Action for Humanity, Lovette collaborates with businesses, policymakers, and institutions to develop equity-centered solutions that are practical, measurable, and embedded in long-term strategy.

Follow Lovette Jallow – DEIB Strategist, Keynote Speaker & Humanitarian:

Website: lovettejallow.com

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/lovettejallow

Instagram: instagram.com/lovettejallow

YouTube: youtube.com/@jallowlovette

Twitter/X: twitter.com/lovettejallow

Action for Humanity Instagram: instagram.com/action4humanity_se

I used to teach in prisons way back when. A lot of the women who were incarcerated ended up on the freedom programme and they were studying the types of abusers, if I recall correctly they were using Lundy. And many came to me and said, quietly, that one of the main lecturers for it, who was male, showed up loud and clear as an abuser.

A LOT of men go into these roles for that reason, because they can perpetuate that control. They will dominate and they will try to abuse, and when, like Llewellyn here found out, they do not get what they want, they spiral, fast.

You are entirely right in everything you have said. I am sorry he is doing this.

I appreciate the insights that you shared about Adolescence. I watched it and saw a lot of what you saw, but you went deeper. I love to watch women stand in their power, and you do not disappoint. Bold and breathtaking. 🎯