Asexuality Isn’t Absence - It’s a Different Kind of Fullness

Asexuality, hypersexualization, and the intimacy of silence in a world that demands spectacle.

Asexuality Has Always Existed—Even Without a Name

Before the labels, there was already recognition. Before I ever knew the word asexual, I had already lived the experience.

In many precolonial African societies, there were people who were not driven by sexual desire. Not out of repression or trauma, but because their energies were directed elsewhere—toward spiritual work, community memory, guardianship, or healing. These were not always women. They were men, women, boys, and girls whose stillness in this area of life was not questioned—it was assigned purpose.

They held roles that required clarity and distance: griots, midwives, rainmakers, shrinekeepers, diviners. People whose lives were structured around protection, language, and lineage rather than sexual or romantic partnership. And still, many were violated. Revered and targeted. Trusted and transgressed. Because even in societies that made space for them, power and control always lingered nearby. Their stillness wasn’t questioned—it was honored.

Sacred roles weren’t sexualized until power distorted them. Their disinterest in coupling didn’t signal lack, but trustworthiness. In some cultures, these individuals were seen as bridges between worlds—not only because of their spiritual work, but because their energy wasn’t being pulled into nuclear pair-bonding. Their lives, instead, were intertwined with community itself.

There was space for people like me long before diagnostic frameworks, long before aphobic jokes, long before Western sex-centric norms took over the conversation.

What I now call asexuality, they may have called a different name. Or perhaps, they simply recognized it without needing one.

Across geographies, I can take you historically to Mesopotamia, Jerusalem, Timbuktu because this pattern repeats.

Lets pause in ancient Greece, Medusa is often misread. But she too was a guardian—of a sacred temple, bound to vows of stillness and autonomy. And when she was violated, her refusal became mythologized as monstrosity. She is not alone. We Black Africans have stories like hers too. Stories of people who refused, or simply didn’t respond—and were punished for it.

So no, it is not strange that someone like me, doing the work I do—carrying memory, shaping language, speaking truth—is not moved by sexual desire when my mind and heart remain untouched. It makes sense. It always has. We just didn’t have the words for it then. Now we do.

This section that follows? It’s not an explanation. It’s a remembering.

What Asexuality Actually Means (And What It Doesn’t)

I once told someone I loved them after sitting in silence for hours beside them, not needing to speak. No declarations. No butterflies. Just stillness. That kind of stillness that rearranges something in you not because they touched you, but because they didn’t need to.

I don’t fall in love the way movies taught us to. There is no lightning bolt. No hunger. No scripted kiss in the rain. What I feel is gradual and slow, but when it settles, it stays. I fall in love when I feel seen—fully, quietly, without having to translate myself.

Which is why I always pause when people ask, “So… are you asexual?”

Because yes, I am. But not in the way most people understand it.

What Asexuality Actually Means (And What It Doesn’t)

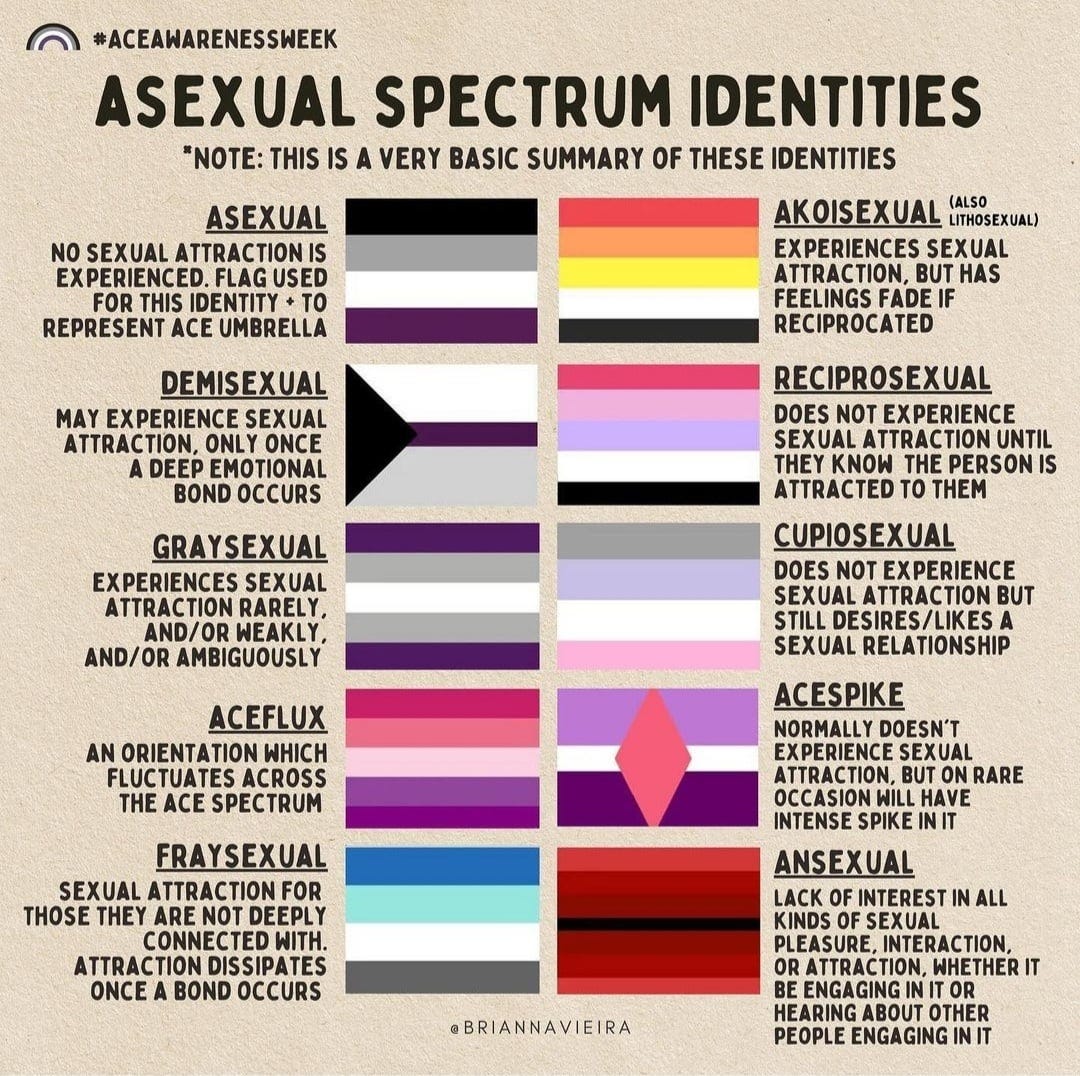

Asexuality is a spectrum, not a sentence.

Let’s begin with clarity: Asexuality is a sexual orientation. That’s it—not a symptom, not a delay, and not a wound.

Some asexual people never feel sexual desire. Others do, but only in specific conditions. Some are repulsed by sex. Some are neutral. Some enjoy it. Asexuality isn’t about fear, trauma, or waiting to be fixed. It’s simply a different rhythm of connection.

It refers to people who experience little to no sexual attraction—but how that looks in practice is wide and varied.

It doesn’t mean we can’t love.

It doesn’t mean we’re celibate—though some are.

It doesn’t mean we’re sex-averse—though some are.

It doesn’t mean we’re broken, traumatized, or waiting to be “fixed.”

The Asexual spectrum: demisexual, graysexual, aegosexual, cupiosexual

And on that spectrum, you’ll find identities like:

Demisexuals, who only experience sexual attraction after deep emotional bonds.

Graysexuals, who feel attraction rarely, weakly, or ambiguously.

Fraysexuals, who feel attraction that fades once intimacy is established.

Cupiosexuals, who don’t feel attraction but may still want sexual relationships.

Aegosexuals (autochorissexuals), who may feel desire but remain disconnected from it.

Some are sex-favorable, some sex-indifferent, and others sex-repulsed.

None of these are contradictions.

They’re simply ways that human intimacy resists standardization—and refuses to be forced into scripts built around dominance, pursuit, and consumption. Reminders that intimacy doesn’t need to follow the same script.

Asexuality is a Different Kind of Fullness—Not a Lack

Sexual attraction isn’t our default setting. It doesn’t structure how we seek connection or determine our sense of intimacy. For many of us on the asexual spectrum, attraction isn’t assumed, automatic, or even relevant in how we experience closeness. And yet, the world reads that difference as deficiency.

People often misinterpret asexuality as a void. But for me—and for many like me—it isn’t emptiness. It’s a different kind of fullness. A self-contained clarity that doesn’t require external validation or performative desire. I abstain not because I’m guarded, but because when there is no emotional alignment, no shared internal rhythm, my body remains still.

There is nothing to withhold, because nothing has been awakened. That stillness isn’t fear. It’s truth.

Being asexual isn’t a wound—it’s a different way of being present in the world. Nothing to be healed from. We need room to exist without being misread. Because Especially when you’re a Black woman. Especially when you’re autistic. Especially when your existence already carries layers of misrecognition.

To be ace in a hypersexualized, neurotypical, gendered society is to live under constant suspicion. Some assume repression. Others infantilize. Many believe that desire is buried deep and just needs the right trigger—persistence, charm, touch. But what they’re actually doing is erasing us. They deny that we’ve already named our truth—and they try to rewrite it to fit their own expectations.

And when that truth comes from a Black woman, the denial becomes more violent. The world doesn’t just misunderstand us. It feels entitled to override us. We are seen through a lens that was shaped by white supremacy, patriarchy, and cultural assumptions about who and what Black women are supposed to be. Neutrality is not afforded to us. Disinterest is not believed. Boundaries are not respected.

For many of us—especially those of us who are neurodivergent or femme—being asexual is not simply an internal knowing. It is a refusal to be consumed. A refusal to perform. A refusal to contort our intimacy into scripts shaped by dominance, by urgency, by extraction. So when I say I’m ace—whether demisexual, graysexual, or something else—it’s not just self-description. It’s resistance.

I’m not confused.

I’m not late.

I’m not broken.

I’m ace.

And naming that truth, in a world that was trained to desire me before it was ever taught to respect me, is a radical act.

Which brings us to the next question—what happens when a Black woman says she doesn’t want you?

The Hypersexualization of Black Women—and the Erasure of Asexuality

Hypervisibility doesn’t equal understanding.

To say “I’m not sexually attracted to anyone” as a Black woman is to rupture a centuries-old script. Our bodies have never been granted neutrality. From colonial caricatures to modern dating apps, Black femininity has been cast as indulgent, hyperavailable, and insatiable—rarely as sacred, uninterested, or autonomous.

Black womens Disinterest Disrupts Fantasies

So when a Black woman says she’s asexual or demisexual—or simply uninterested—the reaction isn’t curiosity. It’s disbelief.

“Are you sure?”

“Maybe you just haven’t met the right person.”

“Maybe it’s trauma.”

“Maybe you’re afraid of intimacy.”

“Your Body language tells me you are interested”

Because to the world, our disinterest isn’t allowed to be ours. It must be corrected, explained, or undone. The same society that hypersexualizes us also pathologizes our refusal. And when we remove ourselves from that gaze, we’re punished—socially, romantically, even clinically. The very act of naming our disinterest becomes a form of resistance.

For asexual and demisexual Black women, the cost is compounded. We are invisibilized in ace spaces where whiteness sets the tone—and pathologized in wider society that cannot accept Black desire as slow, conditional, or absent.

But my truth is this: I do fall in love. But it begins in conversation, not chemistry. In shared silence, not spectacle. In intellectual intimacy that softens into emotional safety.

By the time I feel desire, it’s because I already feel held. And if I don’t feel that? I feel nothing at all. Because my body doesn’t respond to demand. It responds to resonance.

When No Doesn’t Sound Like No—Because You’re Quiet About

Stillness isn’t confusion. It’s a boundary.

She said, “I have enough friends. So dating is what this is.” She said, “You’re impossible to read, you know that?” I nodded, halfway through a dinner I hadn’t even defined yet. She called it a date. I hadn’t.

There was no tension in the air—just her curiosity pressing against my quiet. She watched me like I was a riddle she could decode if she just asked the right questions. But I wasn’t performing mystery. I was holding clarity.

We had a second dinner. I told her plainly: “I think we’d be better as friends.” I already knew we weren’t equally yoked—not emotionally, not spiritually, not energetically. I didn’t feel resonance. I felt obligation. And my body? Still.

She said she had enough friends. So dating was what it would be. And for the next 18 months, we traveled. Sat side-by-side on long-haul flights. Shared hotel rooms and photos and space. But we never touched. Not intimately. Not even in passing. Because there was no desire. No mental mesh. No shared inner world.

To her, we were dating. To me, she was the Imams daughter a companion I had mistakenly let in too close. People think asexuality is about prudishness or trauma or rules. But for me, it’s about truth.

And the truth was: I felt nothing. Not repulsion. Not fear. Just… nothing.

Because my desire doesn’t respond to expectation. It responds to safety, resonance, and recognition. If those aren’t there—nothing stirs. But what I knew deep down—even if I couldn’t name it then—was that connection can’t be pushed into existence.

You don’t earn desire through persistence. You don’t extract affection through presence alone. And you don’t get to bypass someone’s “no” just because it wasn’t dramatic.

Demi sexuality Is Not Just “Being Picky”

Demisexuality is part of the asexual spectrum. It means sexual attraction only happens after a strong emotional connection has formed.

For me, this isn’t some romantic ideal. It’s how I’m wired.I don’t feel desire on sight. I don’t flirt for sport. I don’t “just know” if I’m into someone. My body doesn’t respond before my heart does.

And yet, people misread this as avoidance, fear, or trauma response. But demisexuality isn’t “withholding.” It’s just a different rhythm of connection.

The tragedy is that we often get written off before we’ve even had a chance to connect—because so much of modern dating is built on performance, immediacy, and spectacle. None of which has anything to do with how we love.

And when you’re also neurodivergent, these layers become even harder to explain. Autistic people—especially those of us with alexithymia—may not even recognize desire as it’s happening. It might feel like comfort. It might feel like clarity. It might feel like nothing until suddenly, one day, it feels like home.

I Don’t Flirt—My Body Doesn’t Know How

My rhythm isn’t mystery. It’s clarity.

I was 23 when someone told me I flirted like I was delivering a political speech. Not seductive. Just…direct. Earnest. Almost bureaucratic.

They said it jokingly. I laughed. But inside, I felt that familiar confusion—the one that comes when people expect you to play a game you were never taught, and scold you for playing differently.

I don’t flirt. I connect.

If my mind hasn’t merged with yours in some quiet, layered, nonverbal way, I’m not interested. It’s not mystery I seek, it’s meaning. And I can’t pretend otherwise just to keep up.

The Loneliness of Being Misread as Demisexual

Not falling fast doesn’t mean not falling fully.

I’ve been in rooms where love was expected to look like fireworks and friction. Where wanting more time was mistaken for indifference. Where needing to feel someone’s inner world before touching their body was labeled “too much,” “too intense,” or “too slow.”

It’s lonely to be seen as lacking because your version of connection doesn’t map onto the dominant script. It’s lonelier still to internalize that misreading.

But I’ve learned—through grief, through clarity, and through refusal—that my slowness is not a deficit. It is a boundary. A sanctuary. A way of keeping love sacred instead of performative.

What Love Actually Feels Like—For Me

Recognition before reaction. Home before hunger.

When I love, it happens like this:

Not fast. But deeply.

Not loudly. But irrevocably.

Not for the idea of someone. But for the feeling I get when I’m around their truth.

I fall for their language—the one they use when they think no one is watching. I fall for how they treat silence. How they speak of their past. How they flinch, and how they stay. Love, for me, is slow trust that builds in the marrow. It’s inner-world recognition. It’s shared neurodivergence, not just in diagnosis, but in rhythm, sensory language, emotional pacing.

Sometimes it’s rare. Often it’s wordless. Always it’s chosen.

What If Love Didn’t Have to Look a Certain Way?

I’m not here to convince anyone that asexuality is real. I’m here to remind those of us who live it—quietly, defensively, defiantly—that we’re not alone.

Love doesn’t have to arrive loud. Desire doesn’t have to be instant. Intimacy doesn’t have to follow scripts written by someone else’s expectations. Some of us fall in love through silence. Through consistency. Through shared safety that never demands performance.

And some of us don’t fall at all—not in the ways the world insists we should. That’s not a flaw. That’s a freedom. The more I unlearn the rules I was never built to follow, the more space I make for a kind of love that’s honest. Measured. Chosen. And rooted in truth—not urgency, not spectacle, not hunger mistaken for connection.

So if you’re reading this and you’ve ever felt out of sync with how the world talks about love—if you’ve ever asked yourself: “Why don’t I feel what they feel?” or “Is something wrong with me for needing more?” let this be your answer:

No. You’re just not broken. You’re just built for something else.

Work With Me: Inclusion Strategy, Keynotes, and Critical Conversations

In addition to writing, I work internationally as a neurodivergent inclusion strategist, keynote speaker, and consultant.

I help organizations move beyond surface-level diversity initiatives to create environments where neurodivergent, disabled, and marginalized individuals are genuinely supported.

If your organization, collective, or institution is ready to rethink accessibility, inclusion, and systemic accountability, you can book me for:

Lectures

Keynote speeches

Panel discussions

Workshops and trainings

🔹 Book me: lovettejallow.com

🔹 Contact: Lovette@Lovettejallow.com

Explore More from The Lovette Jallow Perspective

You can find more of my essays exploring:

Neurodivergence, autism, and navigating public life as a Black woman

Building true inclusion beyond checkbox diversity

Reclaiming voice and agency across personal, political, and historical landscapes

Racism in Sweden and systemic injustice

Each essay connects real-world experience with structural analysis—equipping individuals and institutions to think deeper, act smarter, and build sustainable change.

Who is Lovette Jallow?

Lovette Jallow is one of Scandinavia’s most influential voices on systemic racism, intersectional justice, and human rights. She is a nine-time award-winning author, keynote speaker, lecturer, and humanitarian specializing in:

Neurodiversity and workplace inclusion

Structural policy reform

Anti-racism education and systemic change

As one of the few Black, queer, autistic, ADHD, and Muslim women working at the intersection of human rights, structural accountability, and corporate transformation, Lovette offers a uniquely authoritative perspective rooted in lived experience and professional expertise.

Her work bridges theory, research, and action—guiding institutions to move beyond performative diversity efforts and toward sustainable structural change.

Lovette has worked across Sweden, The Gambia, Libya, and Lebanon—tackling institutional racism, legal discrimination, and refugee protection. Her expertise has been sought by outlets like The New York Times and by leading humanitarian organizations addressing racial justice, policy reform, and intersectional equity.

Stay Connected

➔ Follow Lovette Jallow for expert insights on building equitable, neurodivergent-affirming environments.

🔹 Website: lovettejallow.com

🔹 LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/lovettejallow

🔹 Instagram: instagram.com/lovettejallow

🔹 YouTube: youtube.com/@jallowlovette

🔹 Twitter/X: twitter.com/lovettejallow

🔹 Bluesky: bsky.app/profile/lovettejallow.bsky.social

I had to go back and record my own voiceover in my studio. Today I write about what love feels like when you’re asexual, Black, and autistic.

Not the kind built on spectacle or urgency but the kind that waits for resonance.

Stillness before touch. Safety before desire.No butterflies. No chase. Just truth.

What about you?

Have you ever felt out of sync with how the world defines love?

How do you recognize connection when it doesn’t look like the script?

#asexuality #demisexual #BlackAutisticVoices

I hope that people in their teens and twenties can recognize their asexuality for what it is now that people speak of it more openly. Because I didn’t. I thought I was weird, that I just had a low sex drive or that others I knew that particularly high sex drives.

It was only a few years ago that I realized just how different my desire for sex was from allosexuals. I’d started to wonder if I was asexual. I had a single conversation with a friend I live with about his experience of initial attraction to someone compared to mine. And it was so mind blowingly different that I stopped questioning and acknowledged that, yes, I AM asexual.

When I was younger the way we talked about asexuality was very narrow. It was more in line with aroace folks than folks who are ace but also romantic. As such, I never considered that I might be asexual.

People talk about compulsory heterosexuality but few people talk about compulsory allosexuality. It was that compulsory allosexuality that made me, in a small dark corner I didn’t like to look at, think I was strange.

I hope more people talk about what asexuality is and isn’t. I hope younger generations break the chains of compulsory sexualities earlier than some of us did.