Why Autistic Kids Are Punished for Asking ‘Why’ in Religious Spaces

Religious obedience rewards silence and autistic kids come with questions.

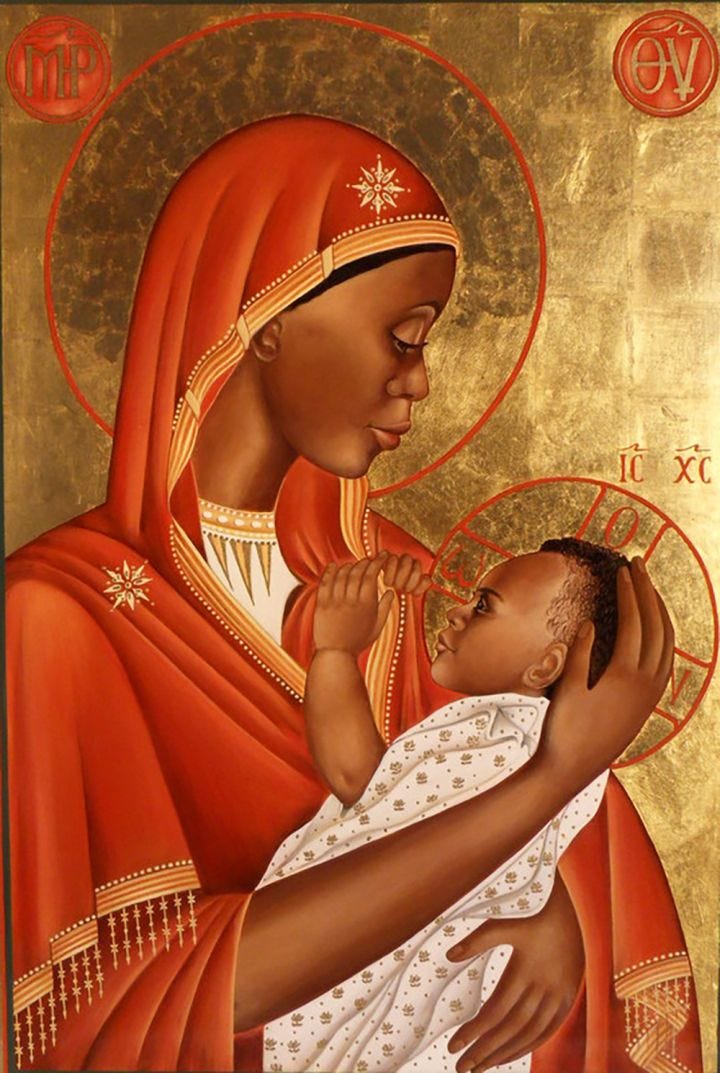

Jesus Was Autistic, and Y’all Would’ve Kicked Him Out Too

Isn’t it funny how everything Jesus actually did would get an autistic kid flagged for “noncompliance” today?

He wandered off from his parents, not to rebel, but to sit with elders and ask too many questions. He flipped tables in sacred spaces when injustice became policy. He ghosted entire crowds when the noise got too much. He fixated on fairness like it was oxygen. He refused fake peace, even when silence would’ve been safer. He held his boundaries publicly, unapologetically even when it made everyone around him uncomfortable. He defended sex workers without sanitizing them. And he was deeply aware of clothing, removing shoes on sacred ground, recoiling from unwanted touch, and weeping over garments torn or cast lots for, because his relationship to the body and what touched it was sensory, not performative.

And yet today, religious communities say “What Would Jesus Do?” while punishing anyone who acts remotely like him. That’s not faith. That’s heresy by omission.

If Jesus showed up in Sunday school today interrupting, questioning, refusing to fake harmony he wouldn’t be praised. He’d be labeled. He’d be sent home with a behavior chart and an incident report.

Just like the rest of us.

I once tweeted something that made people furious:

“It’s not unthinkable that Mary possibly violated by someone powerful said God was the father to survive. The same man who harmed her may have helped prosecute her son when he grew up and spoke too boldly, too clearly, too often. We canonize the story, but we don’t reckon with it. We turn Mary into a symbol of obedience, not a girl whose trauma may have shaped her entire reality. We call Jesus divine, but punish real people who act just like him justice-driven, sensory-intense, unafraid to question power.”

People were outraged. Some laughed. A few became uncomfortably quiet.

Me? I turned it into a story. That retelling “Jesus Was Autistic and Mary Was a Neurodivergent Survivor” won a Christian writing contest.

I wasn’t being provocative. I was being honest.

And to be clear, I’m not saying autistic people are Jesus-like or morally superior. I’m saying the traits we get punished for intensity, honesty, pattern detection, shutdowns, meltdowns, refusal to pretend are the very traits that defined the most canonized figure in Western religion.

What does it mean that we revere those qualities in scripture but pathologize them in real life?

Autism Got Me Kicked Out of Two Cults Before I Even Left High School

I got kicked out of two cults before I even turned twenty. One ghosted me. The other basically held a community vote and decided I was too risky to keep around. Do you know how bad you have to be at conformity to get ghosted… by a cult?

The full saga the one with police reports, secret polygamous marriages (illegal in Sweden), and me scaling a construction site fence like a hijabi ninja—is for another day. That’s autobiography material. Maybe a Netflix one-woman show titled: “CBT Didn’t Work, But At Least I’m Funny.”

Because here’s the thing: when you grow up autistic, especially undiagnosed, you gravitate toward structure. You seek order. You go where the rules are clear and people speak in absolutes. And cults? Oh, cults love a schedule.

And me? I love sameness. I love when everyone wears the same thing. I love assigned seating, repeated chants, predictable outcomes. I love group handbooks with page numbers. I love when information is delivered with conviction—and ideally laminated.

But eventually, the patterns crack. The logic slips. And when you’re autistic, asking “why” isn’t rebellion—it’s survival. That’s when the hierarchy starts glitching. Because I’m not the kind of neurodivergent who just nods along. I’m the kind who studies the doctrine, finds the plot hole, and asks about it publicly… with receipts.

That’s how I ended up exiled from two communities I once found comforting. One removed me quietly. The other stopped inviting me and kept going without me—until I saw photos online. Apparently, they had a baptism event. I guess I wasn’t holy enough for the group text.

But this essay isn’t about cults. That’s for another time and a legal disclaimer I’m not quite ready to write yet.

This one is about established religion. The kind that’s state-sanctioned, tax-deductible, and still managed to kick me out.

Because yes before I was ghosted by cults, I was kicked out of both Quran school and Sunday school.

A two-faith eviction. Baptized and banished. Beatboxed and bounced.

And it all started with one deeply over-scheduled, deeply curious child… and a grandmother who let me keep my “why.”

Autistic and Expelled: My Journey Through Quran and Sunday School

I was born into a mixed-faith family where no one fought over God because everyone already had one. In The Gambia, where over 90% of the population is Muslim, we still cooked for our Christian neighbors, rested on their holy days, and gave out jollof without asking about doctrine. My father’s side is Christian. My grandmother, the family matriarch, was Muslim and went to Mecca twice. We also practiced African spirituality—but quietly, as most people do when colonial religion is watching.

She believed education came before everything, including religious alignment. Which is how I ended up being tutored in multiple systems at once. Monday to Thursday was school. Afternoons were for extra studies. Friday was for Quran school. And Sundays? Well, Sundays were for Jesus.

Now, I was a well-loved, deeply rowdy child with an excellent memory and the attention span of a caffeinated parrot. I spoke several languages—because someone had to translate at recess between Wolof, Fula, and Mandinka kids—and I always had something to say. Most of it unasked for.

Quran school was serious business. The Ustadh (teacher) did not play. We were still on Book 1, the Bismillah. I had memorized it like everything else, but my brain had clocked out that day. Probably because I’d been in lessons from 8:00 to 14:00, then 16:00 to 18:00, and now this. Somewhere between exhaustion and inspiration, I remembered a song I’d seen on MTV. I had the brilliant idea to spice up my recitation with some beatboxing. You know—for rhythm.

So when my turn came, I stood up, adjusted my hijab, and with full confidence began to the tune of Ice Ice baby:

“… bis… bis-millah-ka-ka-ka.”

The Ustadh froze. I kept going.

He lunged for me with a switch in hand. I bolted. My legs, blessed by generations of nomadic Fula blood, launched me over a construction fence like a gazelle in a scarf. Quran school never saw me again. I had officially escaped Islam.

My grandmother was concerned. She gathered the elders. There was a family meeting. Her theory? Perhaps my father’s Christianity had taken root. Maybe the sperm carries religious tendencies? I sat on the sofa, legs dangling, wondering if maybe Jesus had actually infiltrated me from the inside. I mean, he did sound cool. Healing people. Multiplying food. Walking on water. Seemed useful.

So the next Sunday, she took me to church to “observe me.” Test the Christian spirits, as it were.

The church was a towering building with a massive cross and a man nailed to it. I walked in and immediately threw up. Not because of the iconography—I’d just eaten too much jollof. But I could tell the elders clocked it as spiritual resistance.

Still, Sunday school seemed promising. The books were colorful. The stories were wild. And the Jesus guy? He walked on water, flipped tables in temples, asked questions as a child, and didn’t care about being polite when people were being wrong. Neurodivergent king energy. I was sold.

Too sold, apparently. Living in Gambia, surrounded by rivers and sea, I told the kids that if Jesus could walk on water, so could we. We should try it after class. You already know what happened next.

I was labeled a bad influence. The church asked that I not return. My arguments were ignored. And just like that, I was separated from Jesus.

I told my grandmother, “But he’s still my guy.”She told me Jesus existed in Islam too. In fact my own mother shared the same name as Jesus’ mom Mary/Mariam so I am welcome to learn more about “my guy”

I said, “Fine. Run it back. But if that Quran teacher tries to hit me again, I’m biting him.”

And that’s how I ended up in the back row of Quran school not as a Muslim, not exactly as a Christian, but as someone sincerely looking for Jesus. And to be fair, he’s shown up in stranger places since. Including the cults.

Why Autistic Children Struggle with Religious Obedience and Conformity

Here’s the thing: I was never rebellious. I was just autistic in a system that mistook questions for disobedience.

Before I go on, it’s worth noting what happened to me isn’t rare. Research consistently shows that autistic people are often excluded from organized religion:

• 26% of autistic adults identify as atheists, and 17% as agnostic far higher than the general population.

• Children with autism are nearly twice as likely to never attend church, mosque, or other religious services.

• And across traditions, many neurodivergent people report feeling unwelcome, misunderstood, or pushed to perform belief without connection.

It makes sense. Religion often rewards conformity. Autism demands clarity, not compliance. And that tension? It starts early and leaves a mark.

This is also why I reject Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) and its obsession with surface-level obedience. Conditioning autistic children to mimic understanding to say “yes” when their body is screaming “no doesn’t create inclusion. It creates trauma. I wasn’t disobedient. I was trying to stay safe in systems that prioritized submission over sincerity.

They thought I was resisting authority. What I was doing was following logic. Pattern. Cause and effect. I needed to understand the rules so I could know which ones were safe to follow. It’s not “I believe, therefore I obey.” It’s “I observe, I question, I weigh… and then I decide.”

Religion didn’t like that process. Not when it came from a child especially not a Black, mouthy, curious one.

Obedience was the real currency. Even more than belief. Obey, don’t ask. Repeat after me. Memorize the surah. Recite the prayer. Sit still, nod, agree. Ask why too many times and suddenly you’re the problem. The issue wasn’t my theology—it was my tone.

But autistic kids don’t know how to pretend to understand. We don’t feign belief for social harmony. If something doesn’t make sense, we’ll ask about it, urgently, publicly, and sometimes on loop. Because if the logic breaks, so does the safety.

That made me dangerous in settings built on submission. Not because I wanted to cause trouble but because I couldn’t help noticing when the story didn’t add up. I didn’t know how to follow a ritual I didn’t understand. I couldn’t bow to a rule I didn’t believe in. I didn’t want punishment, I wanted clarity. I wanted meaning. I wanted to understand why.

And when no one could answer me, I wasn’t confused. I was done. They called it stubbornness. I call it self-respect.

Because when you’re autistic and asking “why,” it’s not just philosophy—it’s protection. It’s pattern-checking. It’s survival. My questions weren’t about rebellion. They were about staying safe in a world that constantly asked me to comply without giving me the tools to understand what I was complying with.

Religion didn’t fail me because I didn’t believe in it. It failed me because it demanded belief before offering understanding.

And that’s the part no one warns you about. Not the trauma of punishment. But the shame they place on kids who don’t obey fast enough to be holy.

Autism, Faith, and the Power of Questioning Authority in Religion

I didn’t leave religion. Religion left me every time I asked it to explain itself.

I wasn’t searching for salvation. I was searching for coherence. I wasn’t trying to disrespect anyone’s god. I was trying to make sure mine didn’t require me to betray myself.

Every system I walked into from religious school to later cults and even corporate expected me to nod along first and ask questions later, preferably never. But I was born autistic. I ask before I agree. I observe before I participate. I watch the pattern, follow the logic, and when something doesn’t feel safe, I ask “why?”

And if the answer is silence, or punishment, or “because we said so,” I leave. That’s not abandonment. That’s discernment.

I wasn’t kicked out because I was faithless. I was kicked out because I was honest. Because I didn’t pretend. Because I wanted to understand how a god who multiplies fish also demands unquestioning submission. Because I wanted to know if walking on water was metaphor, magic, or something I could try after class.

And I still believe in what I saw in Jesus: a man who flipped tables, fed people without asking for credentials, held power accountable, and never stopped asking hard questions. If that’s not neurodivergence in sandals, I don’t know what is.

I didn’t need a building to find him. I didn’t need a title or a doctrine. I just needed a pattern that made sense and a reason to stay.

And when systems whether religious, cultural, or social ask you to abandon your curiosity for the comfort of their control, let that be your answer.

Because if they can’t answer your “why,” they’re not your people. And maybe the holiest thing you can do… is refuse to pretend.

If This Resonates

You’ll find more of my essays on breaking intergenerational cycles, Neurodivergence and holding boundaries and reclaiming voice.

Matriarchy vs. Gynarchy: Why Replacing Men Isn’t Liberation | Lovette Jallow

Who is Lovette Jallow?

Lovette Jallow is one of Scandinavia’s most influential voices on systemic racism, intersectional justice, and human rights. A nine-time award-winning author, keynote speaker, lecturer, and humanitarian, she specializes in neurodiversity, workplace inclusion, and structural policy reform.

As one of the few Black, queer, autistic, ADHD, and Muslim women working at the intersection of human rights, systemic accountability, and corporate transformation, Lovette brings an unmatched perspective rooted in both lived experience and professional expertise. Her work bridges the gap between theory, research, and action, helping organizations move beyond performative diversity efforts toward sustainable, structural change.

She has worked across Sweden, The Gambia, Libya, and Lebanon, tackling institutional racism, legal discrimination, and refugee protection. Her expertise has been sought by global publications like The New York Times, on high-profile legal cases, and by international humanitarian organizations, where she has provided critical insights on racial justice, policy reform, and equity-driven leadership.

Follow Lovette Jallow – DEIB Strategist, Keynote Speaker & Humanitarian:

Website: lovettejallow.com

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/lovettejallow

Instagram: instagram.com/lovettejallow

YouTube: youtube.com/@jallowlovette

Twitter/X: twitter.com/lovettejallow

I thoroughly enjoyed this. I love essays like this that combine personal story with wider cultural observations, and humour with serious themes.

When you described being kicked out of two religions I was reminded of Baruch Spinoza, who was rejected by Judaism and Catholicism for being similarly difficult—although as far as I know he never vaulted a fence in a hijab.

Lovette, I have appreciated your work every time I’ve read it. But this one? I feel like you put into words the experience that I hadn’t been able to. I absolutely loved it. I would appreciate reading more about your experiences with any ideological groups, religion or otherwise.